Why Planting Soybean Early Improves Yield Potential

Cool and dry accurately describe Nebraska's spring 2014 weather conditions. Al Dutcher, state climatologist, noted in the April 4 CropWatch that "…early spring temperatures are running approximately two to three weeks behind normal."

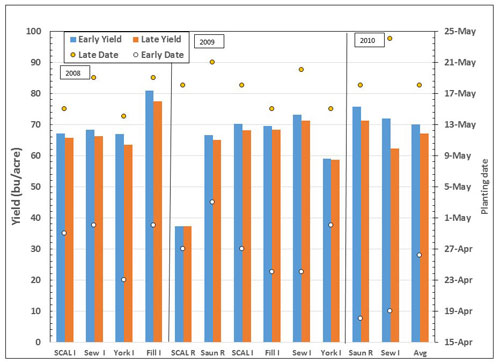

Figure 1. Impact of soybean early and late planting date on grain yield at different on-farm Nebraska locations, 2008–2010. Fungicide and insecticide seed treatments were used for all plots. Use the left vertical axis for yield and the right vertical axis for actual planting dates. SCAL = South Central Ag. Lab, Clay County; Sew = Seward County; York = York County; Saun = Saunders County. The letter "I" in the x-axis labels indicates the site was irrigated; the letter "R" indicates rainfed. Tillage varied by location and included no-till as well as ridge-tilled fields; either 15- or 30-inch rows were used depending on the location. Average yields were different; yields from SCAL Rainfed, 2009, were not included in the average. (Source: Adapted from Table 1, Specht et al. 2012)

Delayed corn planting often results in delayed soybean planting. How does this affect our thinking on planting soybeans and their yield potential?

Historical Perspective

Last year Specht and Grassini well documented that, on average, Nebraska farmers plant soybeans two weeks earlier than they did in 1980. In 1980, half the soybean crop was planted by May 25; in 2012, half the crop was planted by May 11. This trend to earlier planting is likely due to a number of factors, including:

- larger farm sizes that require an earlier start to planting to manage the volume of work;

- increased use of herbicides which has allowed for more reduced tillage systems;

- improved cold tolerance of soybean varieties coupled with seed treatments and climate change — soils warm up earlier than they used to (Pathak et al., 2012, see Figure 2),

- improved planters that allow planting in more diverse situations, and

- underlying all of this is education from UNL research and extension faculty that planting soybeans earlier improves yield potential. Soybean farmers listened and planted earlier.

Impacts of Earlier Soybean Planting

Early soybean planting results in:

- Plants reach V1 earlier in the season resulting in earlier flowering date (R1 growth stage) and potentially a longer growing season. Earlier R1, in turn, increases the length of the seed-fill period. Temperatures drive germination and seedling emergence until the V1 growth stage, i.e., when the first trifoliate has unrolled to the point where the leaflet edges are no longer touching.

- Slower emergence in comparison to later-planted soybeans. Cooler soil temperatures slow hypocotyl elongation; however, this delay is not detrimental to productivity if plant populations aren't reduced to less than 90,000 plants per acre (see Rees, 2012). The most rapid emergence occurs with soil temperatures between 77°F and 95°F.

- More nodes per plant. When plants reach V1 earlier, they accrue more nodes during the growing season resulting in more potential pods and seeds per unit area. After V1, Nebraska research data clearly shows that nodes accrue at about 0.27 nodes per day, or, saying it another way, it takes 3.7 days to produce a new node. Internode elongation is dependent on temperature; in contrast, node accrual is time dependent. Late-planted soybeans accrue fewer nodes than early-planted soybeans. Internode elongation slows after R3 — beginning pod — and effectively ceases at R5 as seed fill begins. Nodes continue to accrue until R5. Although drought stress does not affect the rate of node accrual, it does result in reaching R5 earlier, reducing node numbers and yield.

- Quicker canopy closure with earlier planting captures light earlier and, over the entire season, ensures full interception of solar radiation during the key stages for yield determination (pod set and seed fill). More light "harvested" results in an opportunity to achieve greater yield.

- Greater crop transpiration and less soil evaporation. Yield is linearly related to total transpiration. Early canopy closure reduces weed competition and evaporation from the soil surface and ensures more water available for crop transpiration.

- Similar yields regardless of row spacing. However, narrow rows may be of some advantage with very late planting - late May early June.

- Yield increases of 1/4 to 5/8 bushel per day for each day planting is moved closer to May 1 (Figure 1).

Cautions

- Early-planted soybean attract early-emerging, overwintered bean leaf beetles (BLB). Although some leaflet feeding may occur, the major concern is that BLB transmit Bean Pod Mosaic Virus.

- Early-planted soybean may require a longer time to emerge than late-planted soybeans, depending on soil temperature and soil moisture. Dry soils at planting are not conducive to germination.

- Water deficits later in the growing season inhibit growth and yield regardless of planting date.

- The extent of tillage and amount of residue cover affect soil temperatures. Although soil temperatures during the day don't vary as much with no-till as they do with other tillage systems, early-season soil temperatures are cooler with no-till. Lower temperatures slow the germination process and thus lengthen the time to V1, potentially reducing yield.

- For the first 48 hours after planting both corn and soybean need soil temperatures near 50°F to avoid chilling injury during the rapid water imbibition stage. After the first 48 hours, these crops usually have minimal problems continuing the germination process at soil temperatures well-below 50°F — assuming temperatures remain above freezing; germination will be slower, of course, but if a seed fungicide treatment was applied, there should have be no concerns about loss of germinating seedlings. Monitor your field's soil temperatures on the days preceding planting and on the day of planting plus your forecast temperatures for your area for the next 48 hours to estimate the likelihood of stable or increasing soil temperatures.

Recommendations

-

For More Information

- For Increased Yields Plant Soybeans in Next Few Weeks, Rees and Specht, 2013.

- Soybean Planting Date – When and Why, Specht et al., 2012.

- Drought Avoidance Assessment for Summer Annual Crops Using Long-Term Weather Data, Purcell et al. 2003. Agronomy Journal 95:1566-1576.

Plant soybeans the last week in April in the southern two-thirds of Nebraska and the first week in May in the northern third of the state if soil conditions are suitable and the weather forecast is conducive. Use good judgment. Soil temperature is less of a factor when following these guidelines than calendar date and soil moisture. Regardless of calendar date, neither "mudding in" soybeans — that is, planting when soils are too wet — nor planting in dry soils will turn out well.

- Treat early-planted soybean with insecticide and fungicide seed treatments. These mitigate potential problems from BLB as well as fungal organisms impacting germination and hypocotyl elongation. If soil temperatures are greater than 50°F and the short-term forecast is for warm conditions, insecticide and fungicide seed treatments may not be necessary.

- If corn planting is delayed into late April or early May, use a second planter to plant soybeans as corn is planted, or hire someone to plant one of the crops for you.

- Use short-term weather forecasts to evaluate frost risks at the estimated time of crop emergence.

-

Plant soybeans the last week in April in the southern two-thirds of Nebraska and the first week in May in the northern third of the state if soil conditions are suitable and the weather forecast is conducive. Use good judgment. Soil temperature is less of a factor when following these guidelines than calendar date and soil moisture. Regardless of calendar date, neither "mudding in" soybeans — that is, planting when soils are too wet — nor planting in dry soils will turn out well.For More Information

- For Increased Yields Plant Soybeans in Next Few Weeks, Rees and Specht, 2013.

- Soybean Planting Date – When and Why, Specht et al., 2012.

- Drought Avoidance Assessment for Summer Annual Crops Using Long-Term Weather Data, Purcell et al. 2003. Agronomy Journal 95:1566-1576.

- For Increased Yields Plant Soybeans in Next Few Weeks, Rees and Specht, 2013.

- Treat early-planted soybean with insecticide and fungicide seed treatments. These mitigate potential problems from BLB as well as fungal organisms impacting germination and hypocotyl elongation. If soil temperatures are greater than 50°F and the short-term forecast is for warm conditions, insecticide and fungicide seed treatments may not be necessary.

- If corn planting is delayed into late April or early May, use a second planter to plant soybeans as corn is planted, or hire someone to plant one of the crops for you.

- Use short-term weather forecasts to evaluate frost risks at the estimated time of crop emergence.

Roger Elmore, Extension Cropping Systems Agronomist

Jim Specht, Professor, Agronomy and Horticulture

Jenny Rees, Extension Educator

Patricio Grassini, Extension Cropping Systems Agronomist

Keith Glewen, Extension Educator

April 11, 2014

Online Master of Science in Agronomy

With a focus on industry applications and research, the online program is designed with maximum flexibility for today's working professionals.