Defoliating Insects

Colorado Potato Beetle

Of all the potato insects, the best known and most wide spread is the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) was first observed in Nebraska and then identified in Colorado. It is a well known pest in both commercial fields as well as home gardens. Its host range encompasses all members of the Solanaceous family, such as potato, tomato, pepper, egg plant, and weeds such all nightshades and buffalo bur. It can be a pesky pest defoliating whole potato fields in some parts of North America.

Description

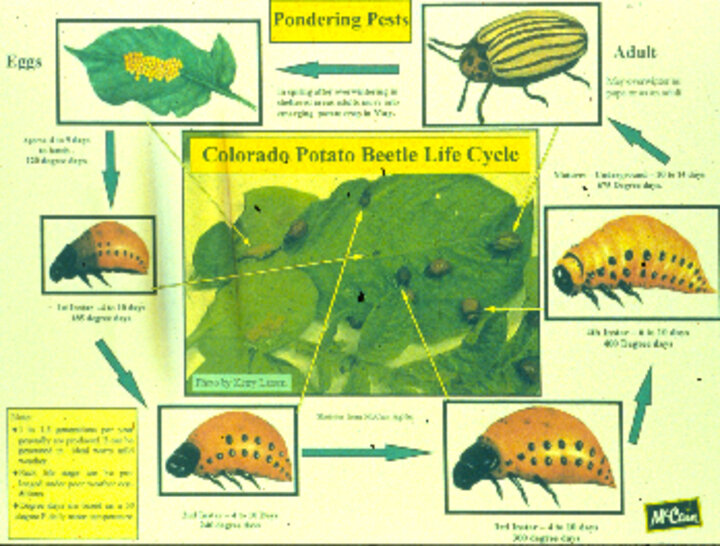

CPB undergo complete metamorphosis: adult, egg, larva, and pupa.

Adults are hard-shelled with a round, convex shape. Their forewings are yellow with a total of 10 black stripes running longitudinal. They are about a half an inch long. Adults eat foliage until they pupate.

Eggs are oval, yellow to bright orange. They are layed in clusters of 10 to 30 eggs on the underside of leaves.

Larvae are slug-like with a soft shell. They are red to orange to tan depending on age and they have two rows of black dots on each side. The body which is humped enlarges with time and grows in four size stages. Larvae eat foliage as they grow and this is the most destructive stage.

Pupae are small and are found in the soil.

Life Cycle

Adults overwinter four to 12 inch deep in the ground of harvested potato fields and emerge in spring around May. Adults do not migrate but will fly for several miles to find its Solanaceous hosts. Besides potato, these include weeds such as nightshades and include garden crops such as tomato and pepper. Adults then mate and lay eggs on the host plants. Egg laying may last as long as a month and may be as many as 500 eggs on a single plant. After four to 10 days depending on temperature, eggs hatch. The cooler the air temperature the longer it will take for hatching. The hatchlings are tiny larva. The larva grow in four progressive stages (instars), eating the host foliage all the while. Depending on temperature, the larval stages will last two to five weeks or when about 400 degree days have accumulated. Then, the larva will go into the ground, three to six inch deep, and pupate. The Pupa last for five to 10 days after which new adults emerge. The emerged adult travels around, looks for mates, and after seven to 10 days begins to lay eggs. The full cycle takes five to eight weeks per generation. Usually, there are two generations per season in Nebraska, early to mid June and early to mid August. In cooler States, less than two generations may occur. At the end of the season, remaining larva move into the soil and overwinter as pupa.

Damage

CPB larvae are the most damaging form but adults also feed on the foliage. Due to feeding, leaflets have holes of varying sizes usually starting around the margins. The leaf blades are eaten often leaving a skeleton of veins and petioles behind. This results in defoliation. Defoliation threshold levels are reported as 25% before tuber bulking, 10% during the first half of bulking, four to six weeks and 25% after bulking. Vine damage results in yield loss due to loss of foliage to support tuber growth and mis-shaping of tubers is also possible. Severe damage may result in plant stunting as well.

Scouting

Monitoring the edges of fields, nearby gardens and surrounding weeds especially nightshades will give warning when CPB are entering the field. Since they are poor fliers, CPB enter a field along the edge usually at a corner that is closest to the previos year’s crop. Economic threshold levels have been reported.

Management

|

* Values are numbers of larval-infested plants per 100 feet of row. Do not apply products unless the average infestation level is greater than these values.

Bechinski, E.J., Sandvol, L.E., and Stoltz, R.L. 1994. Integrated Pest Management Guide to Colorado Potato Beetles. Univ Idaho Coop Ext Circ #757.

Mechanical

The trench method is a semi-successful mechanical control of CPB mostly applicable to small acreage. In areas where close rotations are used or potatoes are grown adjacent to last years potato fields, this method may help to alleviate first generation CPB damage. A trench is plowed between overwintering sites and this year's potato field. The trench should be at least 12 inches deep with sides sloping 45 to 90o. Emerging beetles walk to find their early season hosts and become trapped in the trench. A fine coating of dirt on the plastic prevents the beetles from being able to get out of the trench. Note some CPB adults may fly over the trench; however, this method can be surprisingly effective at trapping beetles.

Using a flamer is another mechanical method for controlling CPB. Its best fit is also in areas where trap crops are used to congregate immigrating beetles for easier control. Flaming is used on plants that are up to 8 inches tall with little adverse effects on them. Larger plants will provide more protection for the beetles and effectiveness is reduced. Flaming involves using two propane-powered flame jets that are directed in an offset manner toward the row. A single unit can be bought for under $3,o00 or constructed. Propane usage is about 3½ to 5½ gallons per acre. Speed is also an advantage. As might be suspected, you don't want to go too slow with this type of machine. A speed of 4 to 6 mph is recommended. Control with the flamer should be done on a clear warm day so the beetles are up on the plants. Data for early-season control have been as high as 90% with this method.

Moyer, D.D. 1992. Fabrication and operation of a propane flamer for Colorado potato beetle control. Cornell Coop Ext Bull. pp. 7.

Olkowski, W., Saiki, N. and Daar, S. 1992. IPM options for Colorado potato beetle. The IPM Practitioner 14:1-21.

Biological

Several common beneficial insects, predators, are good agents for devouring CPB eggs and even attacking larva; see lady beetles and others. Since CPB overwinter in potato fields, rotating crops is key and the following season’s potato fields should be planted a few miles away from the previous season’s potato fields. Since CPB will develop on weeds in the same family as potato, controlling these especially the various night shades is an important part of the management program. Bt products such as Dipel have been used to kill young CPB larvae but timing is crucial for efficacy. In the 1990s, potato clones began to be engineered (GMO) with Bt genes to protect plants from CPB. This technology is very successful in doing that but due to uninformed political pressure this GMO technology has been slowed on potato although common in corn and soybean.

Chemical

Most systemic insecticides applied at planting will kill the CPB's first generation. Most foliar insecticides will take care of later invasions by CPB. The key is not to let the population de-synchronize. If this happens, weekly applications of foliar insecticides could be needed. The best application stage is on the young larvae, first and second instar, because they have most of their eating ahead of them. Older larvae have less eating to do and also are less sensitive. Killing adults works but the result may be so/so because they may have already laid eggs and you may be killing their predators such as lady beetles as well. These predators would devour the CPB egg masses. Since CPB enter fields along the edges and gradually move inwardly, with good scouting, often only the field’s perimeter needs to be treated.

It is very important to note that the CPB is highly capable to develop resistance to insecticide products. On the East Coast and Great Lakes region, the CPB has developed resistance to combinations of products, multiple-resistance or “super” bugs. Therefore, management needs to be an integrated program of biological and chemical methods, at least until the consumer market allows resistant potato lines to return.

Home Gardens

To control CPB in garden potatoes as well as peppers and tomatoes, apply carbaryl (Sevin) to plants when the adults or young larvae are present. But be aware not to treat around flower areas to avoid killing honey bees needed for pollination.

Quick Review

Appearance:

- Adult - round with yellow and black stripping, 1/2 inch long

- Larva - slug-like, pinkish with two rows of black dots on each side, four instars from 1/10 to 1/2 inch

- Egg - small yellow to orange in masses under leaflets

Life Cycle:

- Overwinters as an adult in soil of previous year’s crop

- One to two generations which can de-synchronize easily

- Can appear from April to September

Damage:

- Defoliation; tuber yield loss

Management:

- Crop Rotation

- Beneficial Insects

- Systemic Insecticides

- Foliar Insecticides but beware of resistance

- Bt products

- GMO potato engineered with Bt gene

European Corn Borer

Introduced into North America, the European corn borer (ECB) probably came in "broom" corn from Hungary or Italy around 1909. It was first identified in Massachusetts in 1917 from where it spread west to Nebraska in 1944 as a two-year generation ('bivoltine') strain. Corn is its preferred or primary host but it can infest some 200 plants including dry bean, soybean, and Solanaceous crops such as potato, pepper and tomato.

ECB (Ostrinia nubilalis) is a major pest on corn. As a result, much of the North American corn acreage is planted with Bt-engineered hybrids. Bt-corn is highly effective in controlling ECB, 99% kill as opposed to 75-80% using insecticides. One might assume that this success in corn would lessen the amount of ECB in potato. This may not be the case as recent observations in Nebraska suggest that ECB may be spending more time in potato fields. The increased use of imidacloprid may also play an important role because this active ingredient does not affect ECB larvae (see section on control). Dry summers may also increase the incidence of ECB in potato fields as well (see section on population dynamics).

Description

ECB undergo complete metamorphosis: adult, egg, larva, and pupa.

Adult (not damaging) — ECB are triangular shaped when at rest. They are about three-quarter inch long along their axis. Wings from a distance appear straw colored but male and female vary somewhat in their coloration. Females appear creamy to pale yellow to light brown and have a stout body. Male bodies are smaller and more slender, and the wings are darker than females. The adult wing-span is about one inch and, at rest, they are about a half inch wide. The outer third of the wings are marked by two dark serrated lines running across the wing.

Egg — An egg of the ECB is about half the size of the head of a pin. Color is white or creamy when laid and change to pale yellow and then darken with a "black head" just before hatching. Eggs are deposited on the underside of leaves in masses of 20 to 30 and are covered with a waxy film. The eggs in the mass overlap giving a fish-scale type of appearance. An egg mass is one-eighth to three-sixteenth of an inch long. A female adult lays 200 to 500 eggs during her 14-21 days at a rate of 24 to 40 per day. The eggs hatch in three to 12 days depending on temperature.

Larva (damaging stage) — The larva is light gray to faint pink with a brown to black head, and have small brown to black spots along the sides on each segment and a faint stripe along its back. The body is capsule-shaped and segmented with legs. They grow to about one inch. Larvae are usually found burrowed into potato stems.

Pupa — Pupae are smooth, reddish-brown, cylindrical and about a half inch long. They are found in a chamber burrowed into the stem.

Life Cycle

The strain of ECB in Nebraska is mostly bivoltine, undergoes two generation cycles but in the Panhandle the univoltine strain (single generation) also occurs. The overwintering form is the full-grown larva found usually in corn stalk residue. In Spring, the larva develops and pupates as air temperatures rise above 50 F. The pupal stage lasts two weeks at the end of which the adult emerges. The process is slower at cooler temperatures and accelerates at warmer ones. The adult stage lasts between two and three weeks during which eggs are laid in the evening. Egg masses hatch after about seven days depending on temperature. A few days after being laid, the black head of the developing larva can be seen ("black head" stage). Upon emerging, larvae grow for about a month during which they feed on foliage and bore into the stem. After the month, they will bore and settle inside a stem and pupate. The total life cycle takes eight to ten weeks on the average. Across Nebraska, the first generation or "brood" of adults appears in late May to mid June and damage to potato plants appears toward the end of June. The second-generation adults appear toward the end of July with larval damage appearing in August. The larvae of this generation overwinter. The first generation of the bivoltine strain is normally considered the problem but the second generation can cause storage damage by introducing rot pathogens if they are present in the field. Adults of the univoltine strain appear in early July and their activity is between the two generations of the bivoltine (2-generational) population.

Population Dynamics

ECB populations are lower in dry summers because of their need for water, after extremely cold winters due to freezing and when heavy rains occur during hatching since the larvae drown.

Once moths emerge, chemical treatment should begin seven to 10 days later depending on temperature. Treatments must be applied before ECB larvae tunnel into the stem. The young larvae feeding on the top of the canopy and tunneling more than once may be killed along with adults but the older larvae tunnel deep into the stem and stay there. Scouting for the second generation on potato can be done using traps as with the first but also looking for egg masses on the underside of potato leaflets.

A Possible Key to Population Movement into Potato: Since ECB prefer corn and do not care for potato very much, why do they come into potato fields at all? The key is irrigation and the potato's dense canopy ability to hold moisture. The female ECB has a voracious thirst and requires a daily recharge of moisture. Therefore, it will leave dry corn fields at night searching for wet areas such as potato fields. Once there, the female may decide to lay eggs, foregoing its favorite host for a good water supply.

Scouting and Field Detection

Monitoring European Corn Borer Moth Flight

ECB activity can be detected by monitoring adults using black-light or pheromone traps. Black-light traps are monitored by land grant universities’ Cooperative Extension Service and often reported on Entomology Department’s web-sites. Sex pheromone traps are specific for the ECB male population. Refer to insert by Dr. Gary Hein, UNL - Extension Entomologist. Additionally, moths may be "flushed up" by walking through the field. As moth activity increases, potato stems should be examined for entry holes made by newly hatched larvae.

If the number of corn borer infested stems exceeds 20 per 100 stems sampled, an insecticide application may be warranted. In general, the economic threshold is reported as 15% of plant stems infested. If corn borer pressure is high, a second application may be required 7 to 10 days after the first application, depending on temperature. Rarely are more than 2 applications needed. As long as the initial insecticide application is made at the beginning of the infestation episode, even if some young larvae have penetrated the plant, the overall infestation will be reduced to a level below that at which time the application was made. Young larvae can move around making several holes for a week or so before tunneling deep into the stem and staying there.

While scouting a field, the first symptom that catches attention is a leaf-roll appearance at the top of the plant. Upon approaching the plant, I look to see if the whole plant has this appearance or just the leaves of a particular stem. If only the leaves of one stem show this symptom, I look for the hole that marks a ECB tunnel. At the tunnel entrance, I will find the excrement of the ECB termed 'frass.' It is tan-colored and grainy like fine sand. Splitting the stem will often uncover the larva responsible. On occasion the pupa will be found. Since young larva, early instar, may make several tunnels, it may not be present. Young larvae tend to feed mostly in the upper canopy and leave their frass along the leaflet axil. Older larvae, later instar, bore deep into the branch base.

Damage to Potato

There are several types of damage that the ECB can do. The larvae burrow into the stem eating out the pith and, in the process, also eat the vascular tissue thereby disrupting nutrient flow and resulting in reduced vigor and wilt. A more subtle and, possibly, the major damage is that ECB tunnels have been associated with the introduction of bacterial and fungal pathogens into the plant. The key one is the bacteria Erwinia carotovora the causal agent of black-leg on vines and tuber soft-rot. ECB has been reported to be a vector of E. carotovora and to promote the spread of black-leg in potato fields.

Yield losses due to ECB have been assumed due to the wilting effects of older larvae's burrows. However, published reports from North Carolina concluded that there was no direct correlation between ECB damage and yield of the cultivars Atlantic and Pungo. Yield loss associated with ECB infestation and injury has not been observed often. Yield losses, when observed on occasion, occurred with early-season, pre-bloom, infestation (first generation) and not with mid or late season, after bloom, infestation. When losses were reported, early-maturing cultivars showed over 20% stem infestation and later-season cultivars needed a 50% infestation. Current research on the cultivars Atlantic, Snowden and Superior support these observations (Dr. Brian Nault, personal communications).

Quality losses of tubers were reported as vascular discoloration and as soft rot in storage due to E. carotovora.

Control

Broad-spectrum foliar insecticides are effective in killing adult ECB. Chemical treatment should begin about a week after peak moth flight in corn and a second application made a week to 10 days later. [The peak moth flight is monitored by black-light traps and the peak reading in the sex-pheromone traps occur about a week later which is when treatment begins.] Chemical effectiveness on larvae may be spotty because of the short time that larvae repeatedly tunnel. After adults are first detected in black-light traps, start by examining stems for small entry holes of the young, newly-hatched larvae, first instar. If 15% of the plants have stems with entry holes, treatment is recommended. In-furrow systemic insecticides will NOT seriously affect ECB in potato.

Biological control by predators introduced from Europe is spotty. Ladybird beetles are predators of ECB eggs as well as Col. potato beetle eggs and its population should be encouraged.

Quick Review

Appearance:

- Adult — creamy to pale yellow to light brown; triangular shaped moth; 3/4 inch long

- Egg — white to creamy changes to pale yellow to dark

- Larva — light gray to faint pink with dark head

- Pupa — reddish-brown and cylindrical, 1/2 inch long

Life Cycle:

- Overwinters as larva in corn stalk residue

- Adult females move into potato field in search of water

Damage:

- Adult — none

- Larva — burrows into stem disrupting nutrient flow

Management:

- Monitoring traps

- Scouting for adults

- Biological — lady beetles feed on eggs, control spotty

- Foliar insecticides against adults; little control of larva

False Chinch Bug

The false chinch bug (Nysius raphanus) and/or its damage to potato plants has been seen throughout the mid-High Plains states.

Description

The false chinch bug adult is 1/8 inch and brownish-gray with silvery-gray wings. Their body shape is cylindrical. It congregates on the leaves where it sucks the sap. As many as 100 adults may be on a single leaflet often crawled inside the curl. The adults crawl or fly to other plants after killing the plant top. The adults seem to be the primary concern on potatoes. The nymphs have a brownish-gray head and thorax with a light-tan longitudinal stripe and light tan abdomen with some tiny reddish spots. Nymphs are smaller than adults and are wingless.

Life Cycle

False chinch bugs overwinter as nymphs and adults under debris near winter annuals especially mustards which also act as hosts. Eggs are laid in loose soils or in soil cracks. They hatch in four (4) days. Nymphs feed for about three weeks and reach adulthood. Adults live for several weeks congregating on hosts. There are three or four generations per season with peak populations in July and early August. Crop hosts besides potatoes include small grains, alfalfa, etc. The bugs have even been seen damaging sugar beets. Wild hosts include mustards, kochia, Russian thistle, and sagebrush. Heavy populations build up in these hosts.

Damage

Symptoms seen in fields look like wind burn to upper young leaves. The young top leaves first appear wilting and possibly slightly curled while the rest of the plant appears normal. These leaves rapidly turn brown along the edges and curl. This rapidly progresses with the leaves turning darker and curling tighter until they dry out and are dead. This can occur in a matter of a few days. Fully formed leaves are not affected by these bugs only new growing leaves are attacked. Affected areas can be along field's edge, spots in the field, strips or swathes through the field and in weedy areas.

Adults damage by sucking water from stem. Usually they are found in grains and alfalfa, their preferred hosts, but when these are harvested during the summer the false chinch bugs move to near by potato fields, even a few miles away. In general, the window for potato damage is about three weeks.

Yield losses may occur if large parts of the field are damaged during early to mid bulking when young leaves contribute water and nutrients. Although not reported, some tuber deformation might result from a severe attack at the right time interfering with water movement in the plant.

Scouting

Adults prefer cooler temperatures and are seen on leaves during late evening, 6-8 pm, and somewhat in the early morning. During daytime temperatures, they crawl on the ground under the canopy and into the soil. They are difficult to see because of their brown coloring against the ground. This suggests that the best application of a chemical treatment is by air in the evening.

Control

The best application of control products is during the week after nearby grains or alfalfa are harvested. At that time the false chinch bug will be moving looking for a new temporary home. After a couple of weeks, they will leave potato, looking to return to grains and alfalfa. The damage to young leaves, however, will remain after they leave as there is no recovery. However, new leaves forming after their departure are unaffected.

Little is known about chemical efficacy for control. However, the only product with this insect on the label is Thiodan. A number of growers have given it high marks for its effectiveness. The EC formulation would be applied at 11/3 qt/acre, the highest rate for Col. potato beetle, aphids or leafhoppers. Pyrethroids were suggested in Colorado from work on (true) chinch bugs. A few growers reported poor to fair results. Dimethoate , an inexpensive general foliar insecticide has been effective. Others effective products include Monitor and Provado.

Quick Review

Appearance:

- Adult — brownish-gray with silvery wings; 1/8 inch long

Life Cycle:

- Overwinters in debris near winter annuals

- Three to four generations /season

- Population peaks in July and early August

- Move into potato after grain or alfalfa harvest

Damage:

- Wilting of young top leaves

Control:

- Scouting after grain or alfalfa harvest

- Treat during early bulking if adult population is enormous

Cutworms

Variegated Cutworm

Cutworm is a general term referring to the larval stage of many night-flying miller (Noctuid) moths. Nationally, the most economically important ones for potato are the variegated cutworm (Peridroma saucia), black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon) and spotted cutworm (Amathes c-nigrum). They all have similar habits and appearance; therefore, variegated cutworm is used as the model.

Description

Adults are called miller moths and are usually drab gray or brown but also can be somber yellow and tan.

Larvae are the cutworm which is the damaging stage. Cutworms are caterpillars that when disturbed curl their body into a tight ‘C’ appearance. They have a smooth skin and a wet or greasy texture; their body is plump. The variegated cutworm is grayish brown and lightly speckled with darker brown; it has a single row of pale yellow dots along each side of its body. The black cutworm is greasy gray or brown with faint lighter stripes and granular appearance. The spotted cutworm has a dark stripe along each side of its body and several pairs of triangular-shaped black dashes at the rear of its back. Full grown cutworms are two inches long.

Eggs are small and hemispherical laid under debris, in the soil or on leaves and stem depending on geography.

Pupae are tiny and form in the soil.

Life Cycle

Developing larvae, cutworms, and pupae overwinter in the soil especially from previously grassy areas. Cutworms emerge in the spring. Mature cutworms return into the soil where they will dig a small chamber in which they pupate. Adult moths emerge from overwintered pupae or early-season pupae. Causing no damage, they fly around at night (attracted to electric lights), mate and lay eggs late in the afternoon or at night. Some species lay a single egg or small groups of eggs while others like the variegated cutworm lay closely-packed rows of over 600 eggs. The incubation period ranges from two to 14 days depending on species and temperature. The eggs hatch as cutworms. All cutworms have the same general life cycle; the length of stages varies somewhat. All stages of the variegated cutworm develop rapidly and three or four generations per season are possible. Others may have only one generation per season.

Damage

Initially, spring-emerged cutworms do slight damage by cutting into young stems while eating only a little bit. Unlike, armyworms, cutworms are loners; they do not travel in hordes and are not as prolific. Most cutworms only attack the stems of a few small, often weak, plants. However, the variegated cutworm and a few others will climb up the plant and eat leaves. Feeding is only at night and cooler times of the day. During the day, they hide in soil cracks, or under debris and clods at the soil surface. Their leaf feeding appears as ragged holes or cut-outs in the leaflets. On rare occasions, cutworm feeding on an exposed tuber, leaving shallow holes, has been observed. Economic damage occurs only when there is a high population with intense feeding in the middle of the season during early to mid bulking when plants tolerate up to 10% defoliation. Most foliar damage usually occurs late in the season after bulking when there is little if any effect. Since cabbage and other loopers and armyworms are seen during the day, they may be blamed for cutworm damage.

Management

Biological — Grassland which will be rotated to potato, should be plowed in late summer of early fall thereby reducing the number of eggs deposited. Early fall plowing and clean cultivation will remove debris on which they feed. Cutworms will die of winter starvation or even cannibalism. Do not plant immediately after stubble, grass or sod. In general, cutworms are naturally controlled by parasitic wasps and tachnid flies, and are prone to various diseases.

Chemical — Special chemical treatment for cutworms is discouraged. Soil-applied systemic insecticides used for other pests work well. Since their damage seldom appears until late in the season, it is not economical to treat.

Quick Review

Appearance:

- Adult - night-flying miller moths, usually gray or brown

- Larva - smooth-skinned caterpillars, cutworms, up to two inches

Life Cycle:

- Overwinter as cutworms or pupa

- Up to four generation per season depending on species and climate

Damage:

- Foliar feeding causing ragged holes usually late in season

Management:

- Fall-plowing especially of grassland

- Insecticides used against other, more important, pests

Grasshoppers

Grasshoppers comprise many species. They are not considered major pests in potato fields but when seasonal conditions are favorable, they may migrate into potato and can defoliate sections of a field.

Description

Grasshoppers have large, strong, biting jaws. Their hind legs are strong and adapted to jumping. Their body is elongated and slightly cylindrical. It is partially sheathed by long, slender membranous wings topped with outer leathery wings. Their antenae are relatively short. There are five species that are responsible for most of the damage in North America: migratory, differential, two-striped, red-legged, and clear-winged grasshoppers.

Damage

Grasshoppers are migratory, able to move across a large distance. Their damage in potato is most severe in the central region of the continent, the Plains States and in the mountainous areas of the West. Their greatest damage is by chewing holes in foliage. Damage usually occurs for a short time toward the end of the growing season and there is only one life cycle per year. The outbreaks need to be very severe to cause economic damage in a field but damage can be severe enough along the field edge to cause yield reduction.

Management

Young grasshoppers are controlled by soil-applied systemic insecticides used for other pests. Mid and late season treatment can be limited to the edges of field where grasshoppers are seen. Treatment is seldom required.