Managing Alfalfa Weevil Post-harvest

Generally, alfalfa weevils are cool-weather insects. During this time of year, adult insects would be exiting alfalfa fields seeking cooler spots for over-summering in nearby shady areas or under leaf litter.

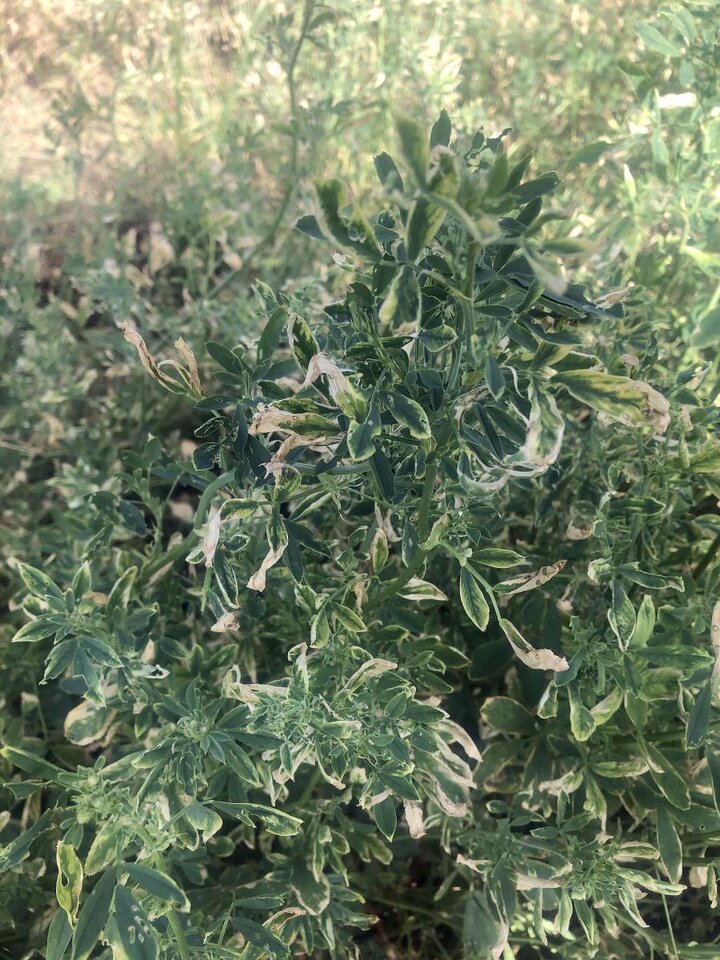

Although our extended cool and wet spring may have favored cool-season plant growth, it has also dramatically increased alfalfa weevil feeding. A second flush of these 3/16” green caterpillar larvae with a white back stripe may be feeding under windrows remaining in wet fields.

So, what management strategies are recommended for late spring alfalfa weevil infestation? In some cases, producers are chopping their alfalfa for silage to reduce field cover for the insects. Usually, weevil development is controlled by hotter temperatures, but cooler temperatures are keeping these insects in the field. Therefore, insecticide treatments with pyrethroids (active ingredient ending in “thrins”) will likely be needed following harvest to aid alfalfa regrowth.

Remember pyrethroid insecticides can also have detrimental effects on any beneficial insects present, so field scouting is still encouraged before making final treatment decisions. Remember that these cool-weather insects seek shelter during the heat of the day, so scouting can be a challenge when they move into the alfalfa crowns seeking shade.

You can find economic threshold recommendations in our Nebraska Extension Guide for Weeds, Insecticide and Fungicide Management (EC130).

Water Demand on Pasture

As the year begins to heat up and cattle are on pasture, it’s important to make sure there is adequate water for livestock. How much do cattle need and where should it come from?

The water requirements for cattle depends on their size, class and environmental conditions. High humidity and greater temperatures also increases water demand.

A University of Georgia study lists water requirements for days when the daily high temperature is 90°F. With these conditions, growing or lactating animals need two gallons of water per 100 pounds of body weight. This means a 1,400-pound lactating cow will need close to 28 gallons of water daily with 90°F daily highs. If the calves are 250 pounds, they will need about five gallons. Again, some of the water will come from grazed forage.

Having fresh, clean water should always be a priority. The ability to have water close by should also be a goal, although sometimes it’s simply not possible. More water locations can help meet the water demand but could also help grazing distribution. Cattle will receive some of their daily water requirements when they are consuming high moisture feedstuffs, such as fresh forages when grazing pastures, silages or green chopped feeds. Feeds that are high-energy increase the water requirement.

Regarding the calf, some water will come from the milk.

Keep an eye on water this summer and make sure livestock have enough.

Stockpile Extra Summer Growth for Winter Pasture

While the amount of spring rain has varied significantly across the state, those areas that have had abundant rain will likely have abundant grass. If this describes your situation, your pastures may produce more growth than needed for your current summer stocking rates. Options to use the extra growth are needed.

Most often, we cut and bale extra growth as hay. This is a good plan if you need the hay, or you anticipate high hay prices this fall and an opportunity to sell that hay. Other times, we simply let cattle graze what they want and leave the excess in the field, rebuilding surface litter.

How about another option? Try stockpiling or saving some extra pasture growth for grazing during the winter.

There are lots of advantages to winter grazing. For starters, less hay needs to be fed next winter. Thus, you won’t need to make as much hay this summer. And stockpiling in summer and fall followed by winter grazing is one of the best methods to improve the health of your grasslands, especially native range. A full growing season without grazing will benefit vigor and reproductive ability of the grasses.

Poor condition and low producing pastures are often the best candidates for winter grazing.

Cattle will do a pretty good job of picking high quality plant parts to eat while winter grazing.

However, as winter grazing progresses, supplementation will likely be needed as the dormant grasses are relatively low in crude protein content.

Extra growth is an opportunity to both reduce winter feed costs and improve pasture condition. Get it by stockpiling extra summer growth for winter grazing.