By Robert Harveson, Extension Plant Pathologist

Pathogen

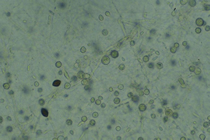

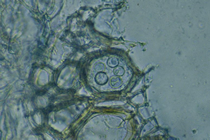

Fusarium oxysporum Schlechtend. f. sp. betae (Stewart) Snyd. and Hans. (Fusarium yellows), Fusarium oxysporum Schlectend. f. sp. radicis-betae (Stewart) Snyd. and Hans. (Fusarium root rot). Teleomorph: unknown. Fungal structures: microconidia, macroconidia, chlamydospores. Both formae speciales of Fusarium are similar morphologically. They survive in soils as globose to ovoid chlamydospores (7-11 µm) and produce both straight to slightly curved microconidia (2.5-4 x 6-15 µm) and crescent-shaped macroconidia (3.5-5.5 x 5.5-21-35 µm).

Pathogens were assigned different formae speciales names to reflect differences in genetic diversity and induced symptoms on sugar beet plants. Yellows is common throughout production areas in the western U.S., and has also been reported in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, India, and Iran. In Oregon beets planted for seed production are often affected by stalk blight due to the Fusarium yellows pathogen. Isolates causing Fusarium root rot were thought to have only been identified from Texas, but new reports of this disease have been made recently from Colorado and Wyoming. There are no known pathogenic races identified for these pathogens at this time.

Disease Symptoms

Older leaves of plants affected by Fusarium yellows first show one-sided wilting and necrosis and interveinal chlorosis. Leaves ultimately become scorched, dry, and brittle. External root symptoms are not present. However, vascular elements in taproots exhibit a reddish-brown necrosis when viewed in cross-section or longitudinal section. Plants regain turgor at night but wilt quickly again during the day, due to vascular elements being blocked with the pathogen. Fusarium root rot also exhibits symptoms that consist of wilting, yellowing and vascular necrosis, but is additionally characterized by a black tip rot at the distal end of the taproot. Often the tip is rotted so severely that only remnants of the vascular elements remain.

Favorable Environmental Conditions

Disease is initiated as soils begin to warm in late spring. Optimum temperatures for infection and symptom development for most isolates are reported to be 75°-80° F. Overwintering chlamydospores, formed in macroconidia or hyphal fragments, germinate and can infect susceptible plants. The pathogen invades roots forming new spores and ultimately reside in the vascular system. High soil moisture is also necessary for adequate disease development.

Management

Genetic Resistance

Few cultivars with tolerance to the pathogen are available for producers in the Central High Plains

Cultural Practices

Practices that attempt to modify the soil environment to the benefit of the plant and the detriment of the pathogen are effective in reducing disease severity. These techniques include planting early into cool soils, and avoiding unnecessary irrigations. Controlling several weeds that can serve as hosts such as pigweed, Kochia, and lambsquarters will also help to avoid large population increases in soils.

Chemical/Biological Control

No effective fungicides are available for producers.

Links

For additional information, see the UNL Extension NebGuide, Fusarium Yellows and Fusarium Root Rot (G1843).