Key Takeaways

LOTS of different stressors this year interacted/combined to cause yield issues.

Photosynthetic stress from pathogens causing leaf and stalk rot diseases were a large contributor.

High nighttime temperatures didn’t allow for deep kernel fill. This, coupled with photosynthetic stress, may have halted kernel development prematurely.

Over-irrigation and/or timing of irrigations most likely contributed to additional disease and compromised root systems that led to reduced yields compared to non-irrigated fields.

This harvest was a difficult one, plagued with breakdowns, slow-going in storm-damaged corn, and disappointing yields in areas of the state. While there were areas of the state reporting average to above-average yields, growers and seed dealers have been asking what caused the 20-40 bu/ac below-average yields experienced in other areas of the state — particularly the York/Seward and surrounding county area, and west-central Nebraska. An email thread amongst the authors resulted in the following article with our thoughts.

Observed Concerns

Common patterns of concern in the York/Seward and surrounding areas included shrunken, lightweight kernels that appeared “shriveled/pinched” at the base of the kernel, southern rust/tar spot on leaves, and high levels of fusarium crown rot/gibberella stalk rots. Corn ears in many fields began prematurely drooping, cutting off the food supply to kernels.

At harvest, some experienced higher or equal non-irrigated yields in corn and soybean compared to irrigated fields. That is nearly always due to too much irrigation and poor irrigation timing, often occurring right before a significant rain event.

In early September, retired University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) Professor of Practice Tom Hoegemeyer shared reports of seed corn fields yielding 15-20% less than anticipated, with small kernels and kernel depth shallower than expected. He felt this was due to exactly the same factors we were noting in irrigated fields in central Nebraska.

“The kernel/ear symptoms are (I think) what one expects from photosynthetic stress,” Hoegemeyer said. “The fact that they appear ‘pinched’ may have to do with timing of that stress.”

Purdue University Professor Emeritus Bob Nielsen added, “Your description of the kernels makes me think that kernel development was prematurely halted.”

Hoegemeyer, Nielsen and UNL Professor Emeritus Roger Elmore all attributed the kernel symptoms to stress occurring before black layer, meaning the kernels may have prematurely died before completing the normal black layer process.

Photosynthetic Stress

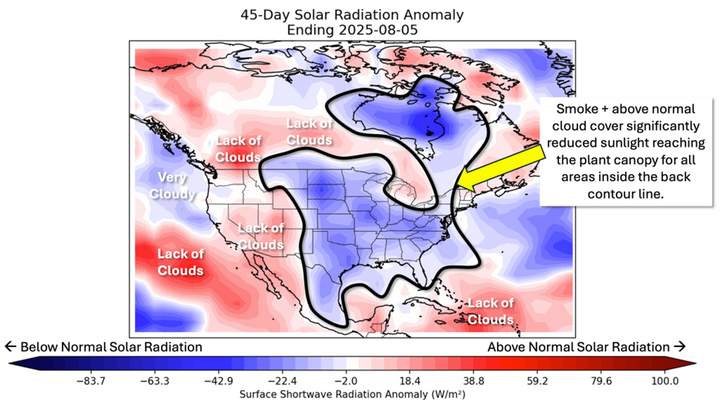

Much of the year we received lower-than-average solar radiation (which includes photosynthetically active radiation or PAR). There were several periods of cloudy/hazy/smoky days (Figure 1). A previous CropWatch article on research utilizing shade cloth revealed 25-30% potential yield loss with shading occurring from R2-R6 stages in corn. That data could explain a potential cause for yield loss.

Dr. Eric Hunt shared solar radiation data for the period between July 4-Aug. 31, 2025, which demonstrated that York, Lincoln and Falls City were running deficits of -21 MJ/m2, -25.2 MJ/m2, and -28.3 MJ/m2, respectively, during the peak of grain fill.

We were hearing reports of above-average yields in portions of northeast Nebraska. The data showed near-normal to above-average solar radiation in that part of the state. Norfolk was below average at -10.7 MJ/m2, West Point was near average at -1.3 MJ/m2 for West Point, and Wayne was above average for solar radiation at +19.7 MJ/m2.

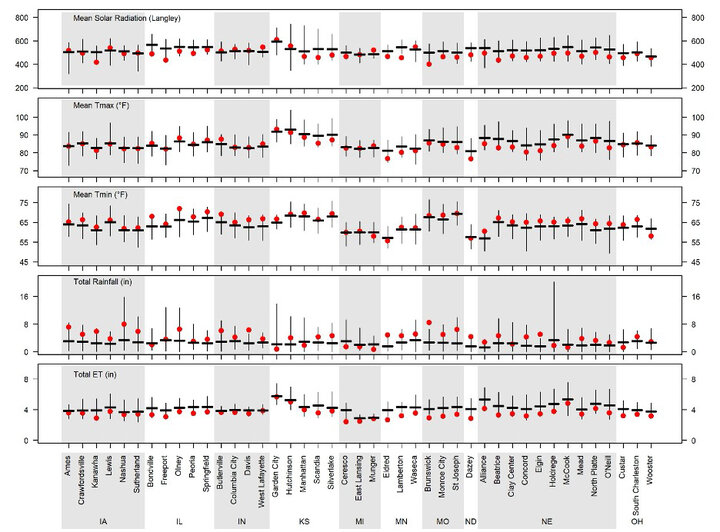

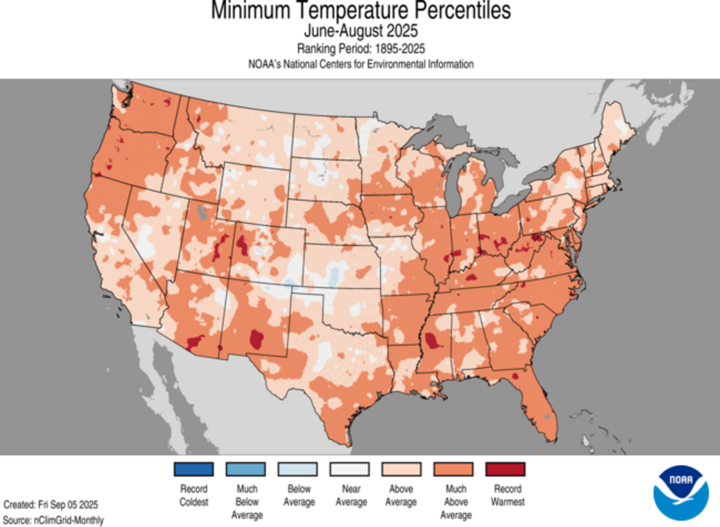

At first glance, the reduced solar radiation during grain fill experienced by several counties seemed to be the major factor impacting yields. Elmore pointed out the 2025 Corn Yield Forecast articles by Dr. Patricio Grassini’s team showed reduced solar radiation, higher nighttime temperatures, and reduced evapotranspiration (ET) for most of Nebraska throughout the growing season (Figures 1-4).

Yet, despite these factors, in the final article, the Hybrid Maize Model was predicting average to above-average yields at the end of the growing season.

“This then points to all the biotic (living) issues you mentioned (as the main driver of photosynthetic stress),” Elmore said. “As Bob wrote, the things you’ve mentioned would, ‘prematurely shut down kernel development.’ The drooping ears is another sign of that.”

Living factors that can create photosynthetic stress on plants include leaf, root and stalk diseases. We feel that irrigated fields had the potential for greater disease, in spite of fungicides applied. Hunt mentioned the high humidity — particularly in York County — due to the sheer amount of irrigation, which may have led to increased disease pressure, including stalk rots.

“I think many producers irrigated prior to and when we got some significant rains during July,” Hoegemeyer said. “Most of the water eventually soaked in but led to even higher humidities and wet leaf areas for extended periods, especially in July and August.”

The spring of 2025 was dry for the York/Seward area of Nebraska and producers began irrigating early to germinate seeds and activate herbicide. This was coupled with producers experiencing drought the previous two years and sometimes the mindset of needing to irrigate.

“Photosynthetic stress and stalk rot go together like beans and weenies,” Hoegemeyer said. “Each one can cause the other. We MAY have had some early infection with Fusarium/gib due to saturated soils/etc. As you know, high N rates, lower K available and a dozen other stress sources make it worse. I think most of the stalk rot is a result of other PS stress, rather than causing it initially, but I am certain that it helped accelerate death.

“I haven't seen cornfields die as fast as they did this year, at least not for decades. And as they died, they didn't die ‘clean’ — lots of disease, top loss reminiscent of pre-Bt days.”

Nielsen added: “Severe reductions in photosynthetic leaf tissue prior to BL (black layer) due to southern rust etc., or early onset of severe stalk rots would also prematurely shut down kernel development. And, of course, … (large) ears with excellent kernel set create a huge demand for photosynthate during grain fill, which exacerbates the negative effects of severe loss of photosynthetic leaf tissue and predisposes the stalk and root tissue to rapid fungal rot infection and development.”

Hot Nights

High nighttime temperatures burn sugars that should go into ears to fill kernels. Figures 2-6 show there were greater than seven-day periods when nights were hot during the grain fill period of July-August.

“If you look at where corn came from (Mexican high valleys, ca. 5,000 feet elevation) days during grain filling will typically be 95 degrees, but it will be 50 or 55 degrees at night,” Hoegemeyer said. “It is the same where we get the highest yields (without doing the crazy fertility, etc., of contests) like the west slope of Colorado and Chile's central valley, they get similar temperatures and relatively low humidity. That's what corn wants.”

Summary

Dr. Tom Hoegemeyer summed it up:

“I think we had lots of issues that caused PS (photosynthetic) stress, some of which impacted our irrigated acres worse than our dryland acres. (My home dryland area had lots of 200 to 220 bpa corn and 65 to 70 bpa soybeans. After a dry spring, we had more rain than we’ve had for years). Irrigated corn in the area often wasn’t as good as the dryland, even with more N applied.

“The more stressors — hot nights, light limitations, too high N for the amount of light/PS–exacerbating disease issues, multiple leaf diseases combined with high humidity, continuous corn, etc. — the bigger the yield loss. And, in some instances, I think adding water to these fields hurt more than it helped.”

Final Thoughts

There isn’t one answer but a combination of factors that impacted fields this year. There’s also a lot of farmers hurting with the combination of low yields, low commodity prices and high input costs. If you’re involved in agriculture or working with those who are, please check in on one another. You’re not alone, and if you’re struggling, help is available — call or text 988, Nebraska’s suicide and crisis lifeline.

We’ve also seen several colleagues and producers announce retirements or begin planning for one. Financial pressure, health concerns and the desire to reduce stress can all play a role in that decision. If someone you know is transitioning out of farming, offer support as they navigate that change. Many find it helpful to retire “to something” by staying active and connected in new ways.

References

- Elmore, Roger, Tom Hoegemeyer, and Todd Whitney. Sept. 20, 2019. How does cool cloudy weather affect corn during grain fill? UNL CropWatch: https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2019/how-does-cloudy-and-cool-weather-affect-corn-during-grain-fill/

- Grassini, Patricio, Jose Andrade, Aramburu Merlos, Haishun Yang, Jenny Brhel, Jeff Coulter, Mark Licht, Sotirios Archontoulis, Maninder Pal Singh, Osler Ortez, Daniel Quinn, Ana Carcedo. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2025-corn-yield-forecasts-july-15/

https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2025-corn-yield-forecasts-aug-5/

https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2025-corn-yield-forecasts-aug-26/

https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2025-corn-yield-forecasts-cooler-weather-seasons-end-increased-forecasted-yields-region/ - Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). September 2018. Field dry-down of mature grain corn. Corny News Network: https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/news/timeless/graindrying.html