Cultural control and conservation help manage the wheat stem sawfly.

The wheat stem sawfly (WSS) has been a major pest of spring wheat in the upper Great Plains throughout much of the 20th century. However, during the latter part of the century, the WSS adapted an earlier emergence period enabling it to infest winter wheat. Over the past few decades, WSS populations have greatly increased and expanded in the Nebraska Panhandle, becoming the most economically significant pest of wheat.

The WSS life cycle begins with adults emerging late-May until mid-June, as adults break diapause and leave the overwintered grass stubbles. Female sawflies then oviposit WSS eggs inside large, hollow stemmed grasses, where the sawfly larvae hatch and subsequently feed on the inside of the host grass stem for about a month. This feeding stress on the host plant can cause a reduction in grain weight and kernel number, resulting in correlated grain yield losses up to 35%. Once the host plant begins to desiccate, the WSS larva stops feeding and crawls to the base of the stem for hibernation, cutting a v-shaped notch in the stem which may cause the grass to lodge.

Chemical pest management with contact insecticides have been shown to be ineffective with WSS control. Alternative planting strategies using solid-stem wheat cultivars have been successful in decreasing WSS larval survivorship, but the seeds are typically more expensive with lower yield returns. Crop rotation has had limited success, partially due to the fact wheat, barley, and rye are simply not being planted. Currently in Nebraska, cultural and conservation control are the two most effective methods of controlling the WSS.

Cultural Control Through Tillage

In dryland wheat, no-till practices can have significant benefits for soil health by reducing soil erosion, soil compaction, moisture loss, and nutrient loss. In western Nebraska, no-till practices became widely used during the mid-2000’s drought. While no-till in wheat may help increase yields from the greater soil health, unfortunately keeping the soil intact may have helped conserve WSS larva overwintering in wheat stubble.

Our results showed a significant decrease in WSS survival with a single pass … [of a tandem disk in wheat fallow].

Our on-farm research from 2016-2018 in Box Butte and Cheyenne counties compared three tillage treatments in the spring on winter wheat fallow previously known to be highly infested by the WSS. The treatments employed were no-till, one pass with a tandem disk, and two passes with a tandem disk. Our results showed a significant decrease in WSS survival with a single pass (approximately 80% mortality) and decrease of WSS survival with a second pass (approximately 95% mortality). Sawfly mortality may be due to simply turning sawfly-infested dirt clods “upside-down,” confusing the emerging WSS adults to which direction is “up” during their emergence from the stubble.

Parasitoid Host Grass Conservation

In addition to employing management strategies within the wheat field itself, selectively planting and/or maintaining specific grasses in the surrounding landscape may also assist in WSS control. Present-day sawfly populations in Nebraska still retain their ability to infest both native and nonnative large stemmed, hollow grasses, but with much lower survivability. Wheat cultivars have been selectively bred to have little height and width variation between tillers. However, non-cultivated grasses still retain much of their original genetic variability, where stem size is highly influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, and soil quality.

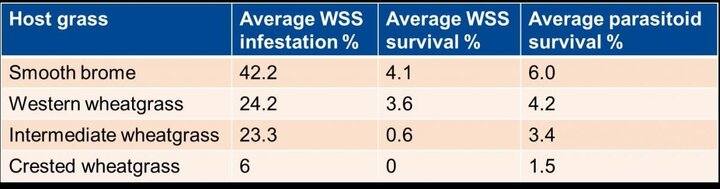

An extensive landscape survey across the Nebraska Panhandle and Sandhills has identified multiple grasses which may work as effective trap crops for the WSS. Host grass preference from most to least is as follows: smooth brome, western wheatgrass, intermediate wheatgrass, and crested wheatgrass (Table 1). However, high infestation does not necessarily equate to high WSS survival. In each of the grasses, a small percentage of sawflies successfully complete their life cycle (Table 1). Alternatively, we have found these four grasses to be adequate hosts for the WSS’s natural enemies, two braconid parasitoid wasps: Bracon cephi and Bracon lissogaster. The conservation of these four non-cultivated grasses may create a situation ideal for trapping sawfly larva within the stem while promoting parasitoid population growth.

… the conservation of these four non-cultivated grasses may create a situation ideal for trapping sawfly larva within the stem while promoting parasitoid population growth.

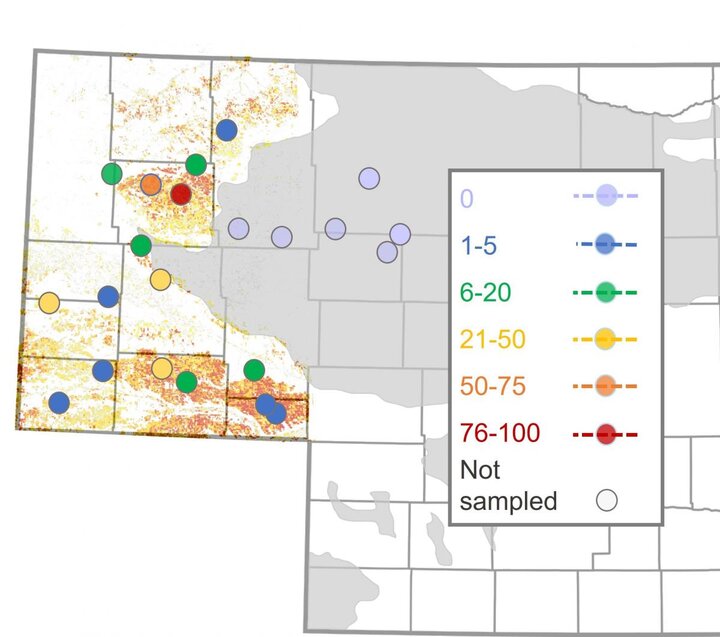

In the parasitoids life cycle, females locate WSS larva living within a stem, stick their ovipositor inside, and paralyze the WSS larva. Then they insect their own egg(s) into the stem to feed upon the WSS larva. The parasitoid may then complete development and form a silken cocoon within the stem, either undergoing a second emergence period later in the summer or overwintering inside the stem to emerge the following summer. Within the landscape survey, we were able to locate this unique relationship between the non-cultivated grasses, WSS, and parasitoid wasps in rangeland, tree-row windbreaks, ditched, CRP ground, and unfarmable areas surrounding power poles (Figure 1).

In order to increase the likelihood of successful parasitoid conservation, growers may consider planting and/or not disturbing smooth brome and wheatgrasses surrounding wheat fields. While the parasitoids were first identified in 2015 at a single location in Box Butte county, the 2019 summer landscape survey found the parasitoids in all 16 wheat fields sampled (Figure 2). These are great results for growers in Nebraska affected by the presence of the WSS.

Closing/Summary

- Moderate, springtime tillage in wheat fallow can greatly reduce WSS emergence from wheat stubble

- Conservation of smooth brome and wheatgrasses on bordering grasslands traps sawflies and increases parasitoid survival

- Every farm operates differently, so considering use one or both strategies may help control the wheat stem sawfly in Nebraska.