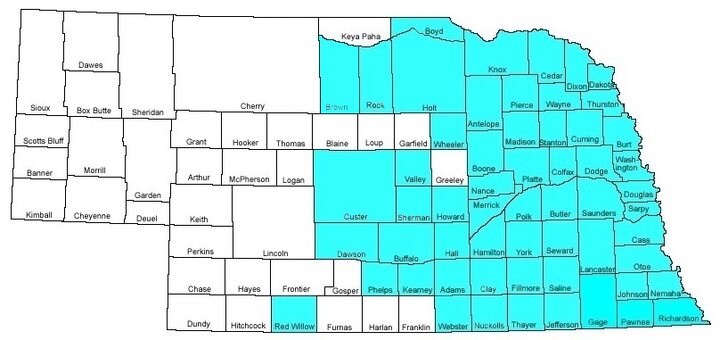

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the first soybean cyst nematode (SCN) identification in Nebraska near Falls City. Since then it has been identified in 58 counties that produce 94% of Nebraska’s soybeans. In that 30-year period, SCN has cost Nebraska farmers over $1 billion in lost yields. Probably at least 90% of those losses came from fields that looked perfectly healthy.

That is what makes SCN such a devastating pest. Yield losses of 25%-30% have been documented in fields with no visible signs of injury on the soybean plants. This is also why SCN detection is so important and the first step in managing it.

There are two ways to detect SCN in the field:

- through a close visual observation of the root system and

- by collecting a soil sample to be analyzed for the presence of SCN.

Visual Detection

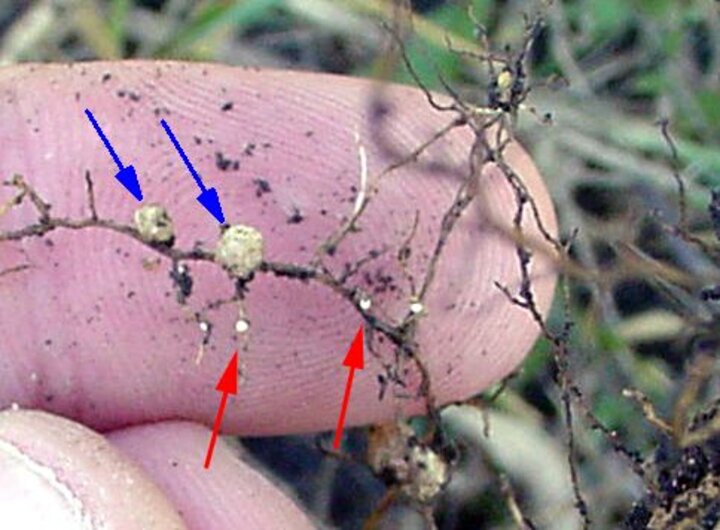

The cyst is the only stage of the SCN life cycle that is visible without a microscope. The cyst, which is about the size of the period at the end of this sentence, is the swollen body of female SCN filled with up to 400 eggs. Cysts start to appear on soybean roots about a month after they emerge. To look for them, dig up plants, then knock the soil off or rinse the roots and carefully examine for cysts. (Dig rather than pull plants to avoid breaking off small roots or dislodging cysts.)

Do this in random spots across the field when you’re scouting for other pests such as soybean aphids or in areas where you’ve noticed plants might wilt sooner, be uneven in height, or appear not quite as healthy as in other areas of the field. Severely stunted, chlorotic or dying plants may signal an extremely high SCN population or several other conditions.

Look closely for small, off white to tan “bumps” on the roots, smaller than the nitrogen-fixing nodules you normally see. Under a hand lens you’ll be able to see they are lemon-shaped. Finding the cysts means you have SCN in your field; however, if you don’t see any cysts, you can NOT say that SCN is not present in your field.

Cysts can be very difficult to detect, especially when populations are low, and they will initially occur in small areas in a field. If you don’t check plants in those small areas, it would be easy to miss detecting them visually. A more reliable detection method is analyzing a soil sample for the presence of SCN.

Soil Sampling

Use the same method to take a soil sample for SCN as you would to take a sample for a fertilizer recommendation. Sample about 6-8 inches deep at random points across a field, mix the soil together, and submit a portion of the composite sample for analysis. If you are taking a sample for your fertilizer recommendations anyway, collect a few more soil cores, mix them all together, and submit half of the sample for fertility analysis and the other half for SCN analysis.

The time to deviate from a composite sample over an entire field (or up to about 80 acres) is if you observe areas in your field where plants look unhealthy or your yield maps showed lower yields that you can’t explain due to soil type, compaction, insect injury, weed pressure, or other stresses. Then take a soil sample from the suspect area and another sample where plants looked healthy or your yields were good and compare the results of these two samples to see if SCN could have caused the problem.

The Nebraska Soybean Board sponsors a program that covers the cost of the SCN analysis (normally $20/sample). Bags to submit samples through this program are available at your local Nebraska Extension office. This is an opportunity for farmers to get a direct benefit on their farm from United Soybean Board Soy Checkoff dollars.

Results from University of Nebraska research trials showed an average six bushels per acre yield increase when comparing SCN-resistant and susceptible varieties on all 29 SCN-infested sites across the state. Yield losses were greater on sandy soils at several locations. They averaged over twice that much, about 12.5 bushels per acre, on five SCN-infested sites on sandy soils in northeast Nebraska.

Resistant varieties significantly reduced reproduction in all SCN-infested fields when compared to susceptible varieties. The best news is, SCN-resistant varieties cost no more than susceptible varieties, but can significantly increase yields. However, these resistant varieties underperformed top yielding susceptible varieties by an average of about 2 bushels per acre when compared to non-infested fields. That is why we don’t recommend planting resistant varieties unless SCN is present in a field.

New Scouting Recommendation

We now recommend testing for SCN about every six years after SCN was first confirmed in a field. By doing this and comparing the egg counts, you can determine if you are effectively managing SCN in your field. It is important to sample at the same time of year and with the same crop in the field or following the same crop to get an accurate comparison.

For example, if you sampled your field in the fall after harvest when soybeans had been planted in the field six years ago, it is important to resample in the fall following soybeans. If your rotation is such that soybeans weren’t planted six years after the initial test was taken, wait another year or two until you are taking the sample at the same time of year with the same crop growing or having been grown in the field.

Hopefully your SCN egg counts will be the same or lower than the counts from the sample taken six years earlier. Follow-up sampling is important as we are finding SCN populations in Nebraska fields that can reproduce on PI88788 varieties, the most common source of SCN resistance.

This source of resistance is found in about 98% of all SCN-resistant varieties commercially available to Nebraska farmers. The SCN reproduction on these resistant varieties is not as great as on a susceptible variety, but it is great enough that farmers are not effectively reducing the level of SCN in their fields. If your egg counts are increasing rather than decreasing and you have planted SCN-resistant varieties, you need to check for a soybean variety that has a different source of resistance or consider rotating out of soybeans for several years, possibly four or five years of alfalfa if that fits in your rotation.

Resources

For more information on detecting and managing SCN in your fields or for bags to submit soil samples for a free SCN analysis, contact your local Nebraska Extension office. Information and videos are also available in the Soybean Plant Disease Management section of CropWatch under Soybean Cyst Nematode.