Bottom Line Up Front

Temperatures this winter are generally expected to be above average statewide, and total precipitation — including snowfall — is expected to be above average in southern Nebraska and around average elsewhere.

Official CPC Outlook

The CPC released its first winter outlook on Oct. 19 with a projection of warmer-than-average temperatures in the northern section of the United States, including northeast Nebraska, and wetter than average conditions across southern Nebraska, with “equal chances” for above-average, average and below-average precipitation across the northern two-thirds of Nebraska. This outlook is strongly weighted to the expectation of a moderate to strong El Niño and its associated stronger subtropical jet persisting through the climatological winter (December-February) into next spring.

Past Precedent

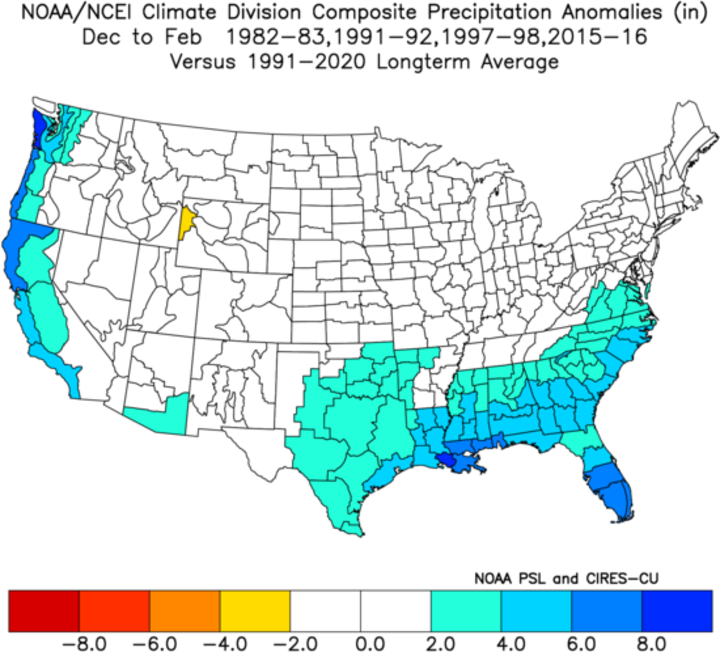

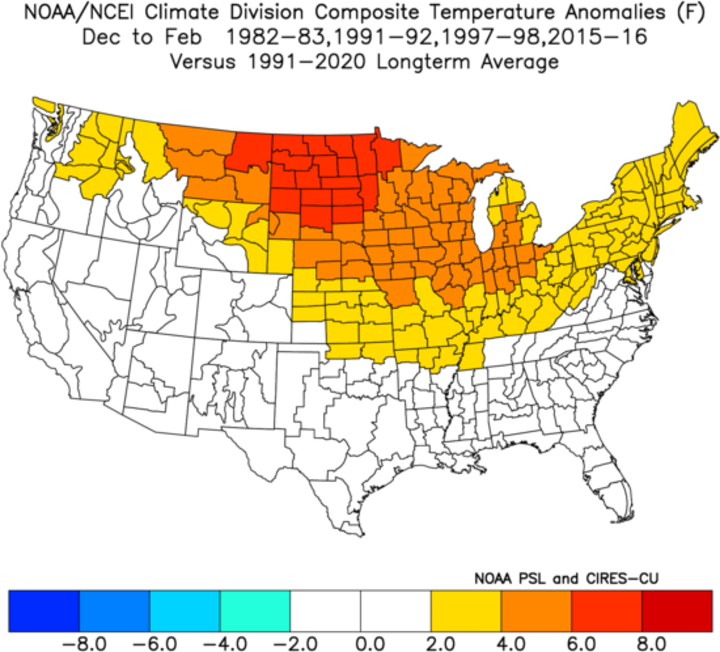

Past precedent would suggest that the winter outlook has a reasonable chance of verifying, particularly on temperature. Of the past six strong El Niños, five were warm to very warm across the entire north-central United States. A composite of the last four strong El Niño events (1982- 1983, 1991-1992, 1997-1998, 2015-2016) reveals temperatures 2-4°F above average in the western and southern climate divisions of Nebraska, and 4-6°F above average in the northern and eastern climate divisions of Nebraska. Thus, higher than usual confidence can be placed on our winter temperatures being statistically above average.

While there is strong signal toward a warmer-than-average temperatures this winter, history would say the outlook is less clear for precipitation. The most recent strong El Niño (2015-2016) was wetter than average in the eastern third of Nebraska thanks to a very wet December. But a composite of the previous four strong El Niño events shows that precipitation was around average across the state. It is worth noting that none of the most recent strong El Niños produced a significantly drier-than-average winter for any climate division in the state.

Drought Outlook

The outlook gives me cautious optimism that we won’t go backward on drought in western and north-central sections of the state where there has been significant drought improvement this year. This would bode well for pastures next spring.

In the eastern section of the state where drought is most severe, total eradication of the drought between now and next spring is not likely. But one anomalous rainfall event on unfrozen soil — as was the case in December 2015 — would significantly improve root zone soil moisture and lead to better pasture conditions in eastern Nebraska next spring. Not that they could be much worse than this past spring.

All in all, it seems reasonable to say that we may chip away at drought a bit this winter in central and eastern Nebraska, but not see radical changes.

Context and Caveats with Seasonal Outlooks

However, there is often more to the story than just the headline and first paragraph. While the winter is expected to be statistically warmer than average and around average for precipitation, this does not mean that we couldn’t have a brutal 10-14 day stretch following a polar vortex disruption (remember February 2021?). It could also mean that being mild is more a reflection of having a lot of days with highs of 37 and a low of 27 because of persistent overcast (particularly in the eastern sixth of the state).

In other words, maybe we trade more bitter cold for more raw cold. It is worth noting that in most of the previous strong El Niños, January tended to be a bit closer to average and either December or February was unusually mild. This would be a bit of a break with recent trends as Januarys have generally been mild and often warmer than either February or December.

Then there is the tendency for a seasonal outlook to be overly bullish on the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO; warm for El Niño and cold for La Nina) state. Using the ENSO state for a seasonal outlook is kind of like predicting team wins for a football team based on its quarterback. No serious football analyst would ignore the skill of a starting QB in making pre-season projections of win totals for the upcoming season, and no serious climatologist ignores the ENSO state for a winter outlook. But just as there is more to having a good football team than just a great quarterback (see the Los Angeles Chargers for evidence), there is also more to an outlook than just the phase of ENSO. While the CPC’s outlook of a warm northern U.S. makes logical sense to me based on past stronger El Niño events and may well verify (especially on temperature), El Niño is not the only game in town.

Other factors besides ENSO can be equally or sometimes even more important for our winter weather. Those factors are, but not limited to, the dominant phase(s) of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), sea ice anomalies, Siberian snow cover in October and November, and sea surface temperature anomalies in the North Atlantic and North Pacific. For example, Phase 1 of the MJO in the winter tends to be wetter and colder in our area (meteorology to English translation: more snow) and Phase 4 tends to be warmer and drier. The extent of Siberian snow cover in the fall has been linked to polar vortex disruptions in the winter, which in turn can favor extreme cold outbreaks into the central and eastern U.S.

Unfortunately, predictability of the MJO is currently only good out to about two weeks. There is some skill at projection of polar vortex disruptions in the sub-seasonal to seasonal timeframe but only so far as to say that conditions are more/less favorable for such an event. For what it’s worth, Dr. Judah Cohen of Verisk Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER), stated in his AO Blog on Oct. 23 that a large disruption could occur around the end of the year. If that happens, our mild winter may be taking a vacation in January, especially in eastern Nebraska.

Be Prepared

Even though an overall mild winter is expected, my best advice for the upcoming winter is to be prepared for the blizzards and rapid swings in temperature by staying on top of seven-day forecasts and not to expect a significant improvement in drought conditions in the hardest hit areas in eastern Nebraska between December and early March.