Key Takeaways

Soil Temperatures: Despite frigid temperatures in February 2025, Nebraska soil temperatures at insect overwintering depths (around 4 inches) remained relatively stable due to insulating snow cover and crop residue.

Impact on Insect Survival: The cold event likely had minimal impact on most overwintering insect pests, as the soil didn’t freeze deep enough or stay cold long enough to kill them.

Scouting Is Still Crucial: Because weather alone isn’t a reliable predictor of pest pressure, farmers should continue regular scouting and monitoring to inform pest management decisions in 2025.

With January and February air temperatures dipping well below zero in Nebraska, agricultural professionals may be wondering if higher overwintering mortality will give them a break from insect pests during the 2025 growing season. Insect survival during the winter is influenced by many factors, including the insect’s biology, agronomic practices, and both the severity and duration of cold temperatures. These factors will be explored in more detail below for three of our state’s key pests: western corn rootworm, western bean cutworm and wheat stem sawfly.

Soil Temperatures Across Nebraska

Soil temperature can vary significantly depending on the time of the season, the amount of snow cover, and soil factors such as depth, moisture, type, etc. Dry, bare soils can vary as much as 10-15℉ in a single day.

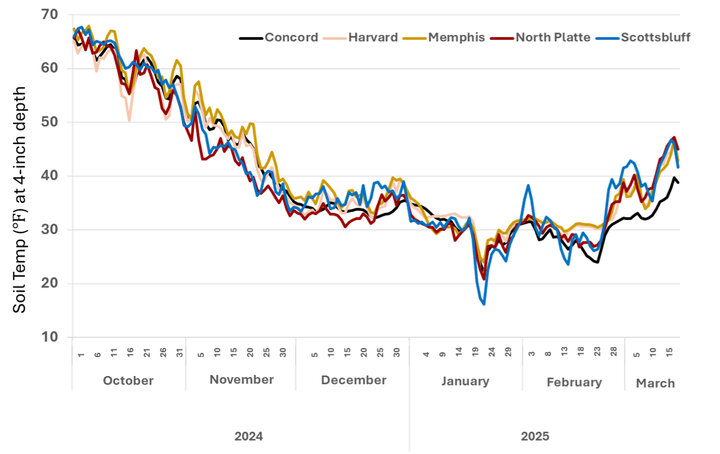

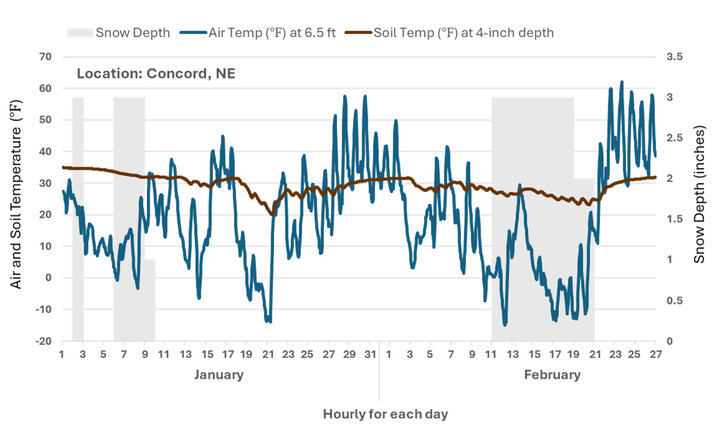

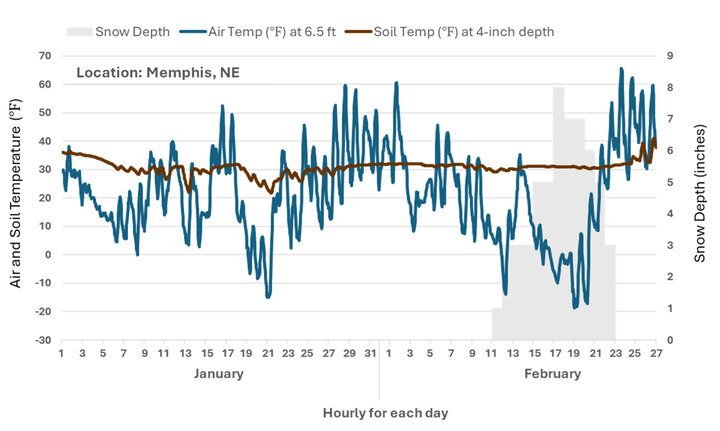

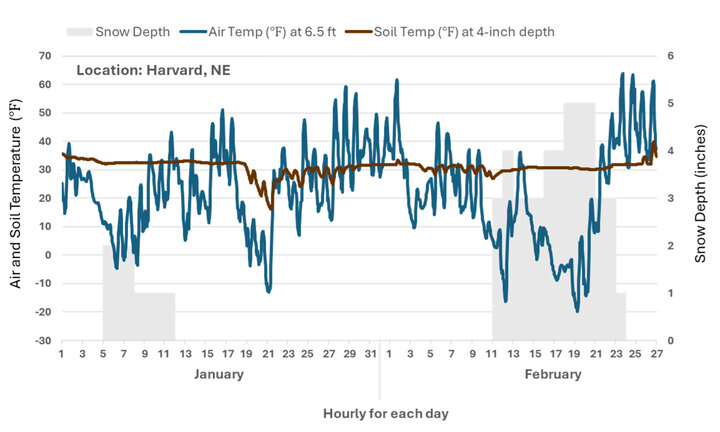

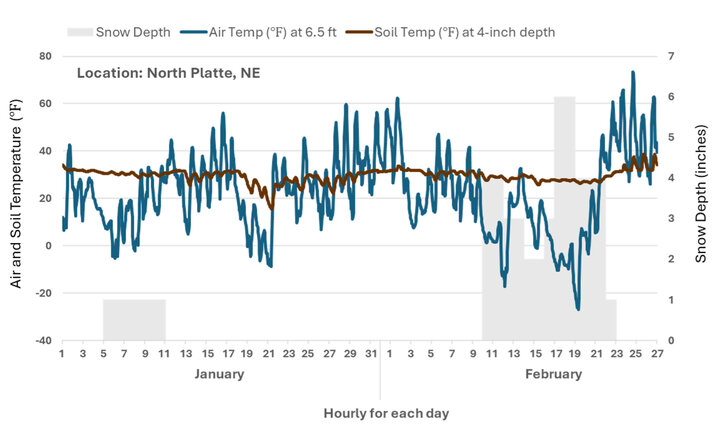

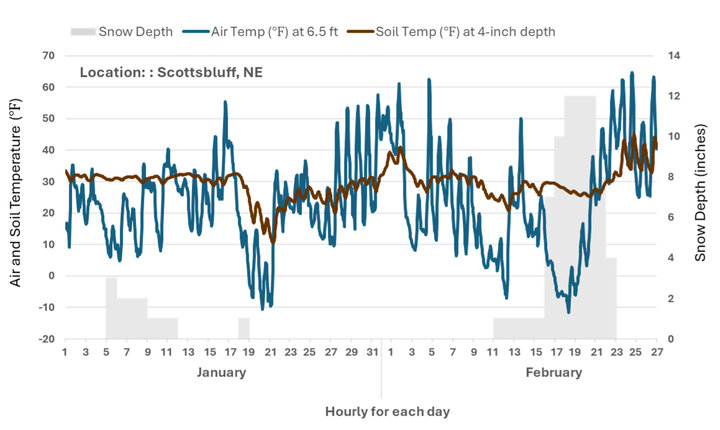

Figure 1 shows the seasonal response in soil temperatures from the High Plains Regional Climate Center at the 4-inch depth near Concord, Harvard, Memphis, North Platte and Scottsbluff. Soil temperatures at these five sites have largely remained at or above 30℉ for most of the winter. However, two cold snaps occurred (one in January and one in February), where air temperature at 6.5 feet dropped down to at least -10℉ at all locations (Figures 2-6).

During January, snow cover was absent or minimal, leading to soil temperatures at 4-inch depth dropping to 15-20℉ in most locations and 10℉ at Scottsbluff. However, these lower temperatures were not sustained for more than several days.

In February, air temperatures dropped even lower; however, soil temperatures remained relatively constant due to the significant snow cover present at that time (3-11 inches across the state).

Western Corn Rootworm

The western corn rootworm (WCR) is an important pest of continuous corn in Nebraska. Beetles can feed on corn silks and interfere with pollination, but it is the larvae feeding on corn root systems belowground that typically do the most economic damage, resulting in poor water and nutrient uptake by the plant and lodging or goose necking of plants.

Female beetles will lay their eggs in the soil of cornfields from late July through September, remaining in the egg stage for the duration of winter and then hatching as larvae in the spring. Most eggs are laid within the top 4 inches of soil, although depths up to 12 inches have been reported. Female beetles hunt for moist places to lay their eggs; under dry conditions, beetles may enter cracks in the soil to find moisture. For this reason, WCR eggs are often laid closer to the soil surface in irrigated fields compared with dryland fields.

Both temperature and moisture can influence WCR egg survival over the winter. For significant mortality to occur, chilling soil temperatures (lower than 14-19°F) must be sustained for longer than one week; the longer the duration of chilling temperatures, the greater the mortality. WCR eggs go through a mandatory period of diapause (a period of suspended development, somewhat like hibernation for an insect) during the winter. A lack of moisture during diapause can cause desiccation (drying out) and contribute to egg mortality. Studies in Nebraska have shown that reduced soil moisture (particularly a lack of precipitation during the winter) can have just as much influence on WCR egg overwintering mortality as cold temperatures during some years.

Various factors interact to affect both temperature and moisture in the field. Egg survival often increases with depth laid in the soil and level of crop residue and/or snow cover depth and snowpack duration. The latter factors act to hold moisture, insulate and moderate soil temperature. High mortality can occur when eggs are laid shallow in bare soil and subjected to dry, cold conditions.

The conditions experienced over the winter in most of Nebraska: average 4-inch depth soil temperatures mostly above 20°F (as indicated in Figures 1-5) should not cause extensive egg mortality. However, during the January cold snap, Scottsbluff did have a brief period with soil temps as low as 10°F. While these temperatures were not sustained for long, if combined with dry soil conditions, WCR egg mortality could have occurred.

Western Bean Cutworm

The western bean cutworm (WBC) is an important pest of corn and dry beans in Nebraska. Moths emerge in early July and lay eggs in these crops, where the larvae hatch to feed, eventually causing economic damage to the developing corn ears or bean pods.

As the caterpillars near completion of the larval stage during August to early September, they will cease feeding and leave their host plant to burrow into the soil. Once they reach a depth of approximately 4.7-10 inches (average 8.5 inches), they construct an earthen chamber cemented with their saliva and enter the prepupal stage (Figure 7). The depth at which WBC overwinter can be affected by soil type — sandier soils allow for deeper burrowing, with a maximum depth reported as 15.7 inches in a sandy loam soil. By overwintering deeper in the soil, WBC prepupae are more protected from cold temperature fluctuations and tillage equipment, leading to higher moth emergence the following season.

The effect of soil temperatures and soil moisture have not been as well-studied for WBC compared to WCR. However, it is known that the super-cooling point (the temperature at which the fluids inside of the insect freeze) of WBC prepupae is approximately 9.3°F. Studies show that WBC are likely not freeze-tolerant, meaning that freezing at 9.3°F will cause death. There has not been much research on the impact of chilling temperatures (temperatures that do not cause freezing but do cause cold stress) on WBC overwintering mortality.

Although more research is needed to fully understand the effects of soil temperatures on WBC mortality and how this may interact with soil moisture and soil type, the soil temperatures experienced by WBC across most of Nebraska indicate that significant mortality of overwintering prepupae is unlikely. However, the brief soil temperatures of 10°F experienced in January in Scottsbluff are likely to have increased mortality of WBC (Figure 6).

Wheat Stem Sawfly

The wheat stem sawfly is an important pest of wheat throughout much of the Central and Northern Great Plains of the U.S. The adult wasps emerge from mid-May through June and lay their eggs within the stems of developing wheat tillers. The larvae hatch within wheat tillers and feed out of sight, largely protected within the stem. Eventually, the larvae move down within the tiller and form a hibernaculum near the crown of the wheat plant. In the process of forming the hibernaculum, the sawfly larvae cut the stem, lodging the wheat to the ground. When the sawfly larvae develop their hibernaculum, they close off the cut end of the stubble (Figure 8: image of sawfly-cut stubble) and surround themselves in a transparent case (Figure 9: image of sawfly pupal chamber).

The sawfly’s overwintering preparations make it highly resilient to cold northern winters. Typically, the sawfly hibernaculum is located in a highly protected location within the wheat stubble following wheat harvest. Prior to the onset of winter, the old crowns at the base of wheat stubble into which the sawflies are hibernating often becomes covered over by crop residue and soil. Additionally, during winter months, wheat stubble effectively captures snowfall which then can further insulate overwintering sawflies from cold air temperatures.

Studies in Montana have shown that sawfly larvae can survive supercooling to -11°F, but that 50% of sawfly larvae die after eight hours at -4°F in the laboratory. However, unless sawflies are exposed to cold air temperatures via fall tillage, the coldest environment that an overwintering sawfly will experience is the temperature at ~4-inch soil depth (Figure 6).

While soil temperatures in the Scottsbluff area were some of the coldest in the state (Figure 1), they were still well above the -4°F or -11°F that would cause 50% or 100% mortality.

Other Insects

Although two of the major pests described above both overwinter in the soil (at depths of 4-8 inches), there are many other species that overwinter at different sites, including on the soil surface, on or inside of plants, in crop residues, and in protected structures like buildings or rock faces. Insects that have overwintered in more exposed areas without insulating snow cover would have been subject to the colder air temperatures in January and likely experienced some mortality. However, some insects have developed amazing adaptations to survive the cold, such as freeze tolerance, where they can physically withstand the freezing of their body liquids, or they are able to produce their own biological antifreeze to prevent body liquids from freezing at low temperatures.

Conclusions

Unfortunately, temperatures at most locations where western corn rootworm, western bean cutworm, and wheat stem sawfly typically overwinter have not reached sustained periods of low enough temperatures to cause considerable mortality. The exception would be the chance for higher mortality of WCR and WBC in January in the Scottsbluff region.

We recommend that scouting and management practices are continued as planned in 2025, and as informed by pest pressures observed in 2024, rather than relying upon this winter’s weather to provide adequate control of pests. However, weather between now and summer could still impact insect survival; for example, very wet soil conditions in spring can reduce WCR survival as larvae hatch out and potentially drown.