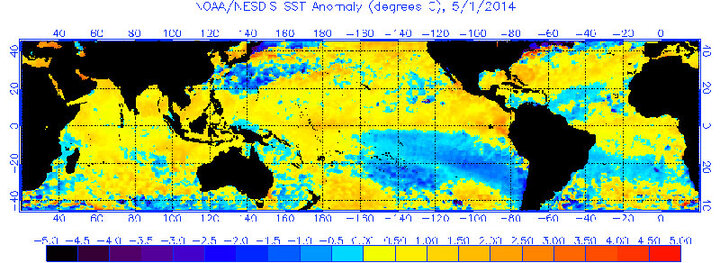

Figure 1. Global sea surface temperature departures as of May 1, 2014.

The national Climate Prediction Center (CPC) recently posted an El Nino watch with the likelihood of El Nino development during the second half of this summer at 52%. The odds of development increase above 70% in the October-November period.

Of the 23 models used to project El Nino / La Nina events, only four indicate this event will reach moderate event criteria. The remaining 19 models indicate it will fall somewhere between a weak and weak-moderate event.

In general, the stronger projecting models develop El Nino conditions much quicker than weaker model projections. CPC has indicated that their forecast accuracy is weakest in the spring and strongest in the fall. The primary reason that CPC is issuing an El Nino alert during the weakest time of the year for forecast accuracy is the 100% agreement by various models that at least a weak event will materialize during the second half of 2014.

I have seen an exceptional amount of misinformation directed to the public in regard to this event and general El Nino trends. First, current weather patterns are not the result of El Nino conditions. Although the Equatorial Pacific has warmed dramatically over the past few months, El Nino conditions have yet to develop.

The recent movement toward a more aggressive precipitation pattern than we saw this past winter is the result of warming ocean conditions along the western U.S. allowing more energy from North Pacific ocean low pressure systems to sweep inland. During most of the winter, waters were cooler than normal and intensified the upper air ridge over the southwestern U.S. and allowed it to expand northward to the Gulf of Alaska. This in turn pushed weather systems into western Alaska and then down the eastern side of the ridge which brought Arctic air to most of the eastern United States.

Second, the primary impacts from El Nino events are felt from the fall through the spring in the Northern Hemisphere. Strong El Nino events usually begin their development in late spring or early summer. Not one of the 23 models used for El Nino forecasting indicates development before the end of July and none of the models anticipate a strong event will materialize.

Figure 1 shows sea surface temperature departures. You will notice that areas immediately north of the Equatorial Pacific are warmer than normal. South of the Equator, a large influx of colder than normal sea surface temperatures continues to be drawn in the Equatorial region from the western Antarctic region. This colder than normal conveyor belt that is limiting the early development of El Nino conditions is expected to continue slow development until at least the second half of this summer.

Third, the typical response during El Nino onset is increased moisture into the southwestern U.S. as evaporated moisture is lifted from the Equatorial Pacific northeastward toward North America. This tongue of moisture can enhance the Monsoon season that usually begins in mid-July in southern Arizona. Additionally, hurricane activity in the eastern Pacific often will ride up the Mexico coast toward the Baja Peninsula, eventually shifting moisture into the southwestern U.S. and enhancing the monsoon season.

Typical impacts in Nebraska during El Nino events include enhanced moisture for the western half of the state during the second half of the summer as Monsoon moisture is moved northeast from the southwestern U.S. into the western High Plains. There is evidence of a slight increase in fall moisture across the southern half of Nebraska as the Southern (Sub-Tropical) Jet begins to dominate U.S. weather patterns and the Northern Jet is displaced well to our north. The Dakotas and northern Nebraska have a greater tendency for drier than normal fall conditions.

The strongest correlations in Nebraska during winter are for above normal temperatures across Nebraska and the northern Plains. A weaker Northern Jet stream is unable to regularly release Arctic air into our region. The main storm track usually occurs with the Southern Jet bringing above normal moisture to the southern and central Plains. The southern half of Nebraska has a slight tendency for above normal moisture, but it is not a strong correlation. There is evidence of a weak tendency for below normal winter precipitation across the northern Plains, including extreme northern Nebraska.

If the El Nino event is able to maintain itself during the spring, such that a multi-year event is predicted, there is an increased drought risk for the northern Corn Belt. The best odds for drought development in Nebraska occur across the northern third of the state, primarily due to the lack of winter and early spring moisture. Multi-year events tend to be moderate to strong during the first year of development and conditions that occur during this period can be magnified during the second year of the event.

Al Dutcher

Nebraska State Climatologist