Bottom Line Up Front

Temperatures this summer are generally expected to be seasonally warm and total precipitation is expected to be below average statewide. Drought is expected to continue and possibly worsen over much of the north-central and western sections of the state. Drought will also continue through the summer in south-central and eastern Nebraska if spring precipitation is inadequate. This season will be like walking a tightrope: There is a path to a solid growing season, but the margin for error is low.

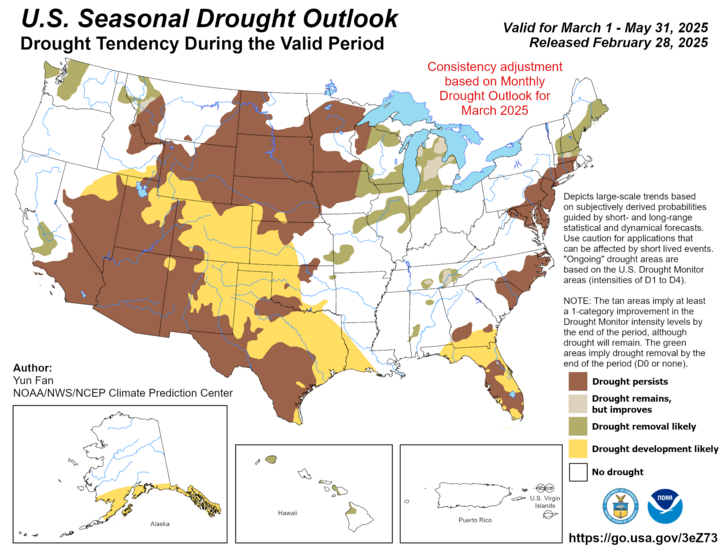

The Official CPC Outlook

The CPC released its latest summer 2025 outlook on Feb. 20 with a projection of warmer than average temperatures and below average precipitation for the entire state. The seasonal drought outlook (good through the end of May) shows that all but the far southeastern corner of the state will be in drought as we head into summer.

How Concerned About Drought Should I Be?

The answer to that question is clearly operation-specific in a literal sense, but in a general sense, the answer is that it depends partly on how this spring goes. The official forecast from the CPC favors drier than average across the western three-fourths of the state and no strong signal on temperature. The spring after a winter La Nina often features troughing being more dominant in the Pacific Northwest, with ridging more prevalent in the southern and eastern U.S (Figure 4). If we are able to get a series of deeper, slowing moving troughs into the western U.S. this spring, then that opens up the possibility of getting more significant precipitation across the state. Later next week looks promising but we need that train to keep coming.

In much of south-central and eastern Nebraska, a wetter spring would be enough to end the drought. It means the winter wheat crops will have good moisture to bring it home, and the corn, soybean and sorghum crops will have a reserve. For reasons that I will discuss in a bit, that reserve of moisture may be critical as we head into the heart of summer.

For the rest of the state, increased precipitation would mean improvement. Given the depth and severity of existing drought in the Panhandle and parts of the Sandhills, it is unlikely that enough precipitation would fall over the next several months to end the drought. But it may be enough to give the winter wheat crop a chance at improving, a shot a good start for corn, dry beans and sugarbeets, and it would greatly benefit pastures.

However, should significant precipitation not materialize this spring in the hardest drought hit areas, 2025 will likely be very challenging for ranchers and grain farmers alike. It is essential that moisture be adequate this spring or it's going to be slim pickings in many pastures for the cattle this summer across the western and northern sections of the state. Recommend checking out the GrassCast website (see related links) for more detailed forage projection scenarios starting in early April.

Further south and east in the prime corn/soybean ground where drought conditions are comparably more mild, a dry spring will mean starting out the summer with only a marginal reserve of soil moisture at best. That would not bode well because there is little indication that this summer will be a statistically wet one anywhere in Nebraska, or across most of the western Corn Belt and Central/High Plains for that matter. But there is a potential silver lining.

2021 Weather to the Rescue?

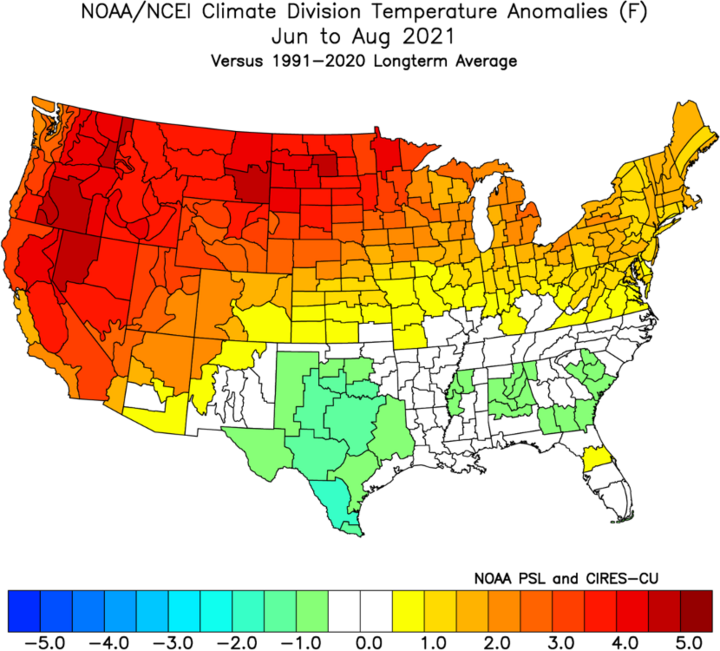

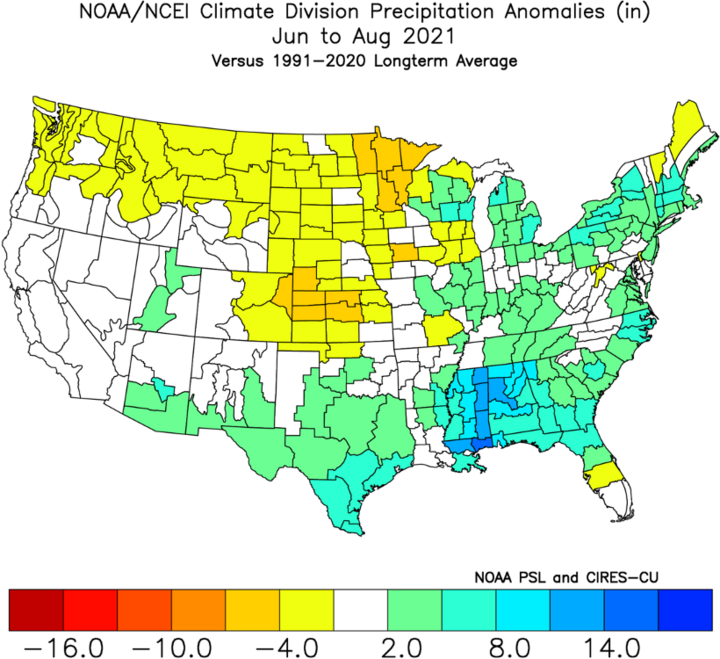

When looking at the official projections of temperature and precipitation this summer across the country from various modeling centers, it does remind me of 2021, at least to a point. The upper air pattern that summer tended to feature ridging over most of the northern and western portion of the continent, which made for a statistically warm/hot and dry summer across a lot of the north-central and western U.S.

That summer was famous for the intense heat in the Pacific Northwest in June and for extreme drought in the Northern Plains, including the very northern fringe of Nebraska. But for a lot of us in the state, it was perhaps the best growing season so far this decade. How was that possible?

Four things made that possible. First and foremost, March 2021 brought drought-busting rains and solid soil moisture recharge to a majority of the state. That meant the reserve was stronger heading into summer compared to most recent years. Second, because the ridging was not anchored over the upper Midwest, it meant that there were still frontal passages coming in periodically and the heat was not centered over us for any long period of time. Third, there also was access to Gulf moisture that summer. Between access to Gulf moisture and latent moisture in the form of crop ET, frontal passages were generally able to produce precipitation.

Translation: Most of us got timely rains in mid- and late summer. Finally, most of the heat that summer was front-loaded in June and the grain-filling period featured more optimal temperatures. It is worth noting that 2021 was a pretty good year in the 'I' states and most projections this summer are for more favorable conditions in the central and eastern Corn Belt than in the western Corn Belt and Central/High Plains.

A pattern that resembles 2021 is certainly possible. But the moral of the story and my point in the previous paragraph is that season was very conditional. If that spring had been drier, my guess is most of the state would have been experienced a summer that was closer to 2020 or 2022 than the one that helped produce record yields. Rationale for that is frontal passages might have been coming through with less precipitation thanks to a lack of locally sourced soil moisture and ET, as happens in our drought summers (for example, northeastern Nebraska in 2022). If the heat in the summer of 2021 had been three weeks later, it is hitting during the beginning of pollination instead of mid-June. In other words, we could have atmospheric features that resemble 2021 and end up with outcomes that are significantly different if a few key details are different.

What I'm Watching For

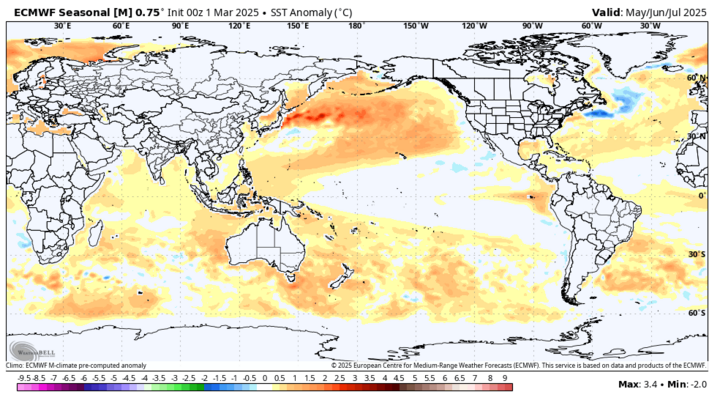

I will be watching several things as we head into summer. The first is the sea surface temperatures (SSTs). The current projection is for more neutral ENSO conditions, warmer water in the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, and colder water off the coast of Nova Scotia. The lack of a strong La Nina signal heading into the summer is good news for us, as La Nina tends to not be our friend regarding moisture and temperature in the second half of summers.

The lack of a distinct cold signal in the SST seasonal forecast between the Gulf of Alaska and northern California gives me some confidence that there won't be a persistent trough off the Gulf of Alaska this summer. I care about that because a trough between Anchorage and Seattle generally means there is a persistent downstream ridge somewhere in the central section of the continent. That means our area is cut off from atmospheric forcing that can help generate precipitation and it tends to be hot.

The SST pattern shown above in Figure 7 would (in my opinion) favor a western ridge. But the average position of a western ridge center is important. It is more favorable for Nebraska if it is centered over Seattle. If it's displaced over to central Montana, then most of Nebraska tends to struggle with precipitation while the eastern half of the Corn Belt tends to get moisture and cooler temperatures. If the ridge is to our south, as it was for much of the summer in 2023, we tend to be in and out of heat with periods of time where we get ridge riding storms. If by some miracle that ridging is over eastern Alaska, then we would be enjoying a summer with a lot of nights in the 50s and highs in the low to mid-80's and timely rains.

I will also be watching the placement of the Bermuda High this summer. If it is near Bermuda, we can get good moisture return from the Gulf back into the central U.S. If it has wandered over to the Azores or Iceland, then we are not going to get optimal moisture flowing back into the central U.S. and would make the Corn Belt much more dependent on locally sourced moisture. A combination of an eastward displaced Bermuda High and upper-level ridging living between the Rockies and the Great Lakes all summer is a recipe for drought intensification and heat over the entire region like we had in 1983, 1988 and 2012. That is not the most likely scenario this summer. But if there are signs for this combination coming to fruition in May and we have not had adequate spring moisture, we could be headed for something as bad or worse than the years listed above.