Wet weather that persisted during the early 2024 growing season was very favorable for development of some corn diseases in Nebraska. In particular, diseases caused by fungi were favored by repeated rainfall events and high relative humidity, fog, etc. that supported the production of more spores and continuous plant infection. On some susceptible varieties and hybrids, diseases developed early and quickly. In some areas, disease severity is increasing, but in most areas, diseases are still at low severity and not a threat to yield.

Foliar fungicides were applied to some fields to mitigate losses due to disease or in pursuit of plant health benefits. However, low commodity prices and narrow profit margins make foliar fungicide application decisions more difficult as producers weigh the application costs and the uncertainty about what to expect from diseases (and growing conditions) through the remainder of the season.

Summarized below are the most favorable conditions and biological features of southern rust and tar spot.

Southern Rust (Puccinia polysora)

- 77–82°F is optimal

- At least six hours of >95% relative humidity

- New pustules develop in as little as seven days after infection

- Each pustule produces thousands of spores for about seven days

- Yield loss up to 45% in severe cases

- Spores turn black during late season and may be confused with tar spot

Tar Spot (Phyllachora maydis)

- 60–70°F is optimal

- At least seven hours of >75% relative humidity

- Visible black stromata develop 12-15 days after infection

- Yield loss can be 0-50 bu/acre

- Strongly favored by overhead irrigation

Recent questions have emerged about disease development after fungicide applications. One of the most important factors to consider when making a foliar fungicide application is the timing of the application and how long you can expect protection from the product.

In general, most FRAC Group 11 QoI (formerly called strobilurins) and FRAC Group 7 SDHI fungicides are expected to provide about 21-28 days of protection of leaves from infection by some fungi. Group 3 triazoles can provide some systemic or locally systemic curative activity, but only for infections that have just occurred in recent hours or couple of days. Thus, fungicides applied a day or more after infection will not stop all lesion development and some disease development may still be observed.

Locally, some agronomists and producers are reporting substantial disease development in the lower leaves where conditions are more humid and favorable, or where the fungicide application didn’t fully penetrate the canopy to the bottom leaves of the plant. Fungicides can’t restore or heal diseased plant tissue. And, unfortunately, gaining an economic return on the foliar fungicide application is determined by several additional factors that impact future disease development making the decision more difficult, such as:

- Disease history (for those pathogens that overwinter here — everything but rust diseases)

- Susceptibility of the hybrid or variety

- Weather forecast

- Use of irrigation

- Crop stage

- Crop rotation vs. continuous cropping

- Tillage practices

According to research results from Purdue University, the most effective application timings for management of tar spot in Indiana were those made between full tassel emergence (VT) to blister (R2). Applications made after early dough stage for either tar spot or southern rust are much less likely to provide an economic return except in extreme cases with severe disease.

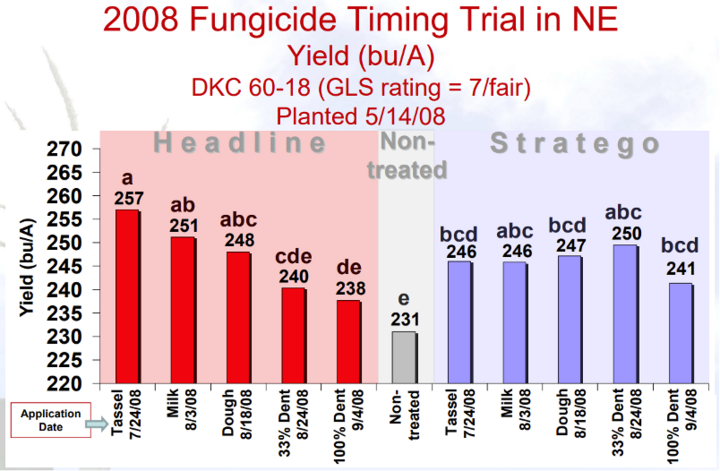

Fungicide timing trials were conducted in 2008 at the South Central Ag Lab near Clay Center with two corn hybrids varying in gray leaf spot disease ratings and with Headline and Stratego fungicides. In the later planted treatments (April 30 vs. May 14), both fungicides provided yield increases over the nontreated control under substantial gray leaf spot pressure in the more sensitive hybrid when they were made as late as early dough, but not beyond that timing (Figure 4). There was little southern rust pressure in that trial.

The protection provided by most foliar fungicides will wear off within three to four weeks, leaving crops vulnerable to increased disease severity later in the season. Applications made too late in disease development will likely not provide the desired level of control. This may also be impacted by the seeming delay in development of disease symptoms from earlier infections.

Some pathogens may require up to three weeks for symptom development after infection (called the incubation period), which often occurred during an earlier period when weather conditions were more favorable. (Similarly, the latent period varies for each pathogen and refers to the time from infection to pathogen reproduction or sporulation.) Fungicides applied during this time won’t likely be able to stop lesion development if the pathogen infected the crop more than a couple days prior to application. Thus, producers may notice some increase in disease symptoms soon after a fungicide application.

The development of disease lesions after product application may give producers the impression that the products didn’t work as expected, but it’s important to keep in mind that fungicides — especially those containing active ingredients with Groups 7 and/or 11 — protect healthy leaf tissue from infection for a period of time, and slows disease development and potential impact on grain fill and yield.

Second Fungicide Applications

Given the anticipated protection window of most products is three to four weeks, if a second fungicide treatment is needed, it should be made three to four weeks following the first one. Second applications are much less likely to provide an economic return except in the cases of severe disease pressure.

Corn Diseases to Watch

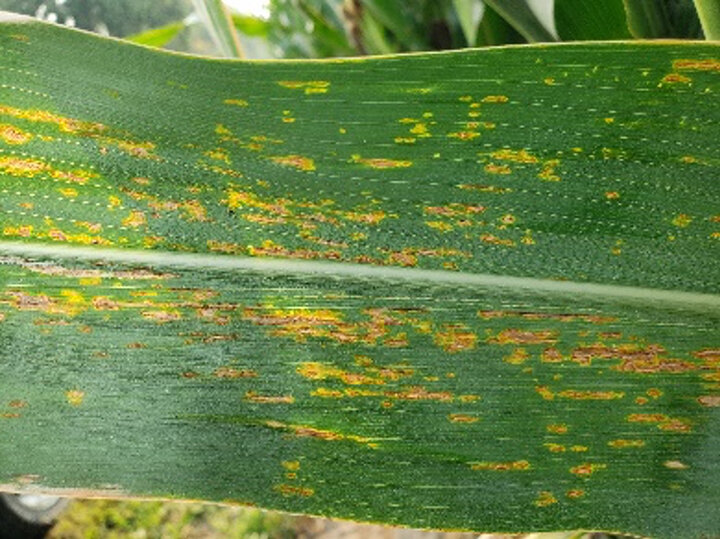

Southern rust (Figure 1) continues to be identified in corn fields across eastern Nebraska, with samples confirmed from most eastern counties. However, there has been little evidence of significant increases in southern rust severity in these areas, possibly due to hot, dry conditions in recent days creating less favorable conditions.

Tar spot (Figure 2) has continued to be found at low to moderate incidence and severity in most locations, with a few additional counties added in recent weeks.

It’s important to continue to scout regularly during the early grain fill stages to monitor for rapid changes in disease incidence and severity, and consider whether a fungicide may be helpful. The southern rust and tar spot that is active in the lower canopy of fields still has the potential to increase significantly under very favorable conditions for either disease.

Unfortunately, bacterial leaf streak (Figure 3) has continued to spread and increase in some fields and corn hybrids across Nebraska. Be careful not to confuse these wavy lesions with those of gray leaf spot. Bacterial leaf streak can’t be controlled with fungicide applications.