The clock is ticking for Nebraska Mesonet.

Weather stations are being dismantled and stashed, gathering dust on the shelves of indefinite storage. Nebraska Mesonet personnel have shut down seven mesonet stations across the state so far this year, with another 10 slated to go dark by the end of December — and it’s just the beginning of a steady decline with far-reaching implications, all triggered by one enduring catalyst: funding.

“I’m out of money. I don’t have any savings,” said Nebraska Mesonet Manager Stonie Cooper. “We can’t operate in the red.”

The Mesonet’s Mark

So, what exactly is the Mesonet, and what does it do for you?

When the Nebraska Mesonet was formed in 1981 — notably one of the first statewide weather monitoring networks in the nation — it was done so with the agricultural community’s needs in mind. Over the years, however, and with the addition of new technologies, Nebraska State Climate Office Director and State Climatologist Martha Shulski said they’ve transitioned the Mesonet into a much broader environmental monitoring program.

“There are lots of pieces to that ‘pie’ — the users of (Mesonet) data today,” Shulski said.

Nebraska’s weather stations are now equipped to process hourly readings on a considerable amount of weather conditions. Adorned with various instruments, each tower measures temperature, humidity, precipitation, wind speed and direction, solar radiation, barometric pressure, and soil temperature and moisture levels.

This data has continued to benefit Nebraska farmers and ranchers in their daily operations since the Mesonet’s inception, but over the years, numerous organizations have joined its clientele base. Chief among those entities is the National Weather Service (NWS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Drought Mitigation Center, the Nebraska Department of Natural Resources (DNR), USDA Farm Service Agency (USDA FSA), Nebraska Extension — the list goes on.

Precipitation data is easily the Mesonet’s most-demanded and versatile product, used for everything from planting and management of irrigation, pests and weeds, to monitoring risks such as livestock heat stress, drought, flash flooding and fire hazards.

However, data points like wind speed and direction are rapidly growing in interest as producers seek to prevent pesticide/herbicide drift. Crop insurance companies have long used wind data to verify claims. Numerous national products, such as the National Drought Monitor, also use local data compiled by the Mesonet to build environmental reports.

Seemingly innumerable, the full extent of applications for Mesonet data have yet to be identified, Shulski noted. Unfortunately, such extensive use also means that even one closure can present significant barriers for organizations relying on Mesonet data.

One such agency is the Upper Elkhorn Natural Resources District, where General Manager Dennis Scheuth said four of the five weather stations in the NRD’s proximity have been removed.

Disconcerted about the closures, Scheuth explained the National Drought Monitor, in particular, is a byproduct of Mesonet data that’s crucial to the Upper Elkhorn NRD’s functions.

“That information is used very heavily with Natural Resource Districts,” Schueth said. “(It’s) used to look at where we have been, where we’re moving forward over a time period, seeing if we’re using more or less water. That all affects the models that we’re using, and we need accurate data to project into the future.

“The more stations you have, the more accuracy you can determine in the weather, so (accuracy) is going to be hindered on the Drought Monitor.”

The result, Schueth said, will be impediments for the University of Nebraska, the State of Nebraska and local NRDs to efficiently manage groundwater and surface water in the state.

The trickledown effect of losing four weather stations means producers in northern Nebraska will likely also experience obstacles when it comes to water management.

“We use the weather stations to determine evapotranspiration (ET) … to inform producers how much ET their crop is using, and they use that to curtail how much irrigation they’re putting on these crops,” Schueth added. “It really became an educational tool for those producers, to help protect our water supply.”

Evapotranspiration is just one of many Mesonet data points that Nebraska Extension Water and Integrated Cropping Systems Educator Nathan Mueller uses in his daily communication with producers of southeast Nebraska. In the spring, Mueller responds to a steady stream of calls about planting dates by checking Mesonet soil temperatures, and he scans soil moisture data to build his weekly USDA crop report — a task performed by most extension educators.

“Weather is so integrated with crops in our positions, like freezing temps, soil moisture — it’s all helpful from an awareness standpoint,” Mueller said. “When people call, they expect us to know those things.”

Despite its immense significance, utilization and sponsorship of the Nebraska Mesonet seem to be on opposite ends of the spectrum.

'We can’t come up with a champion for the network that will value its importance enough to fund it.'

Funding Shortfalls

The Mesonet is currently funded through a variety of channels, including Nebraska Department of Natural Resources (DNR), UNL’s Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources (IANR) and School of Natural Resources (SNR), and a group of individual sponsors that represent different sectors of the ag industry.

In 2016, when Cooper and Shulski were tasked with upgrading the Nebraska Mesonet into a “viable, national-class mesonet,” they were bestowed a budget from IANR, SNR, Extension and DNR of $276,000. That sum, however, has decreased over time. With funding losses, and sponsorship from industry stakeholders ever a moving target, the Mesonet’s financial health is floundering.

“We can’t come up with a champion for the network that will value its importance enough to fund it,” Shulski said.

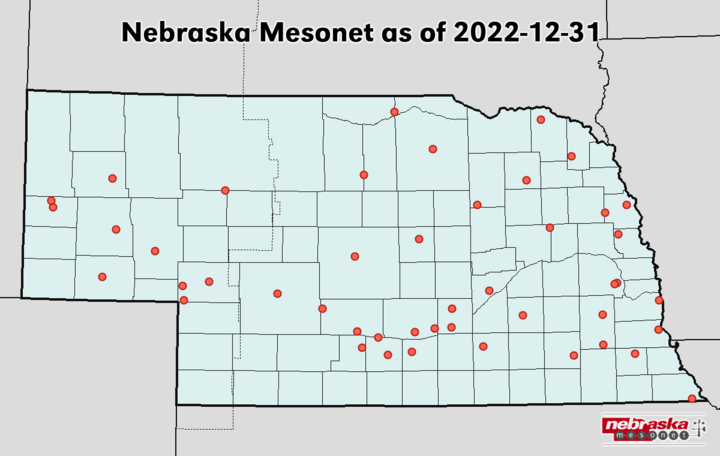

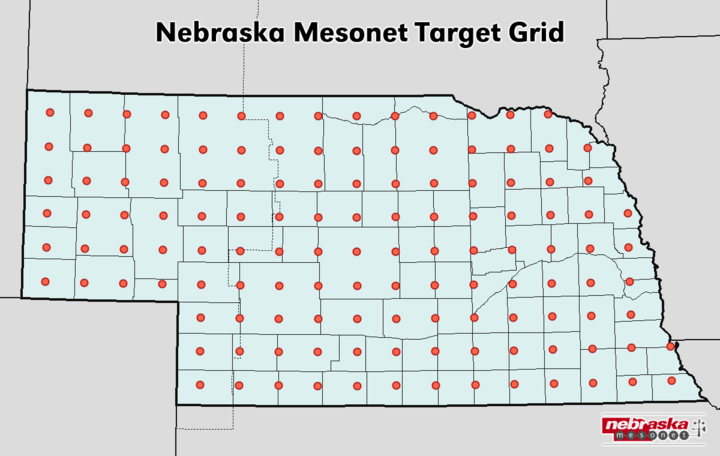

Moreover, the funds that sustain the Nebraska Mesonet fall far short not only of current operating expenses, but also the sum required for a fully-fledged weather monitoring network, according to Cooper. In its 31 years, Nebraska Mesonet has never achieved full capacity on weather stations — 81 is the historical maximum, with an annual average of 70. Today, there are 55 active stations.

“We need $550,000 to keep our bare minimum operation (for current stations) — that’s not going to get us to the 130 stations that we need for appropriate monitoring,” Cooper explained. “We’re non-profit, but we also can’t operate at a deficit.”

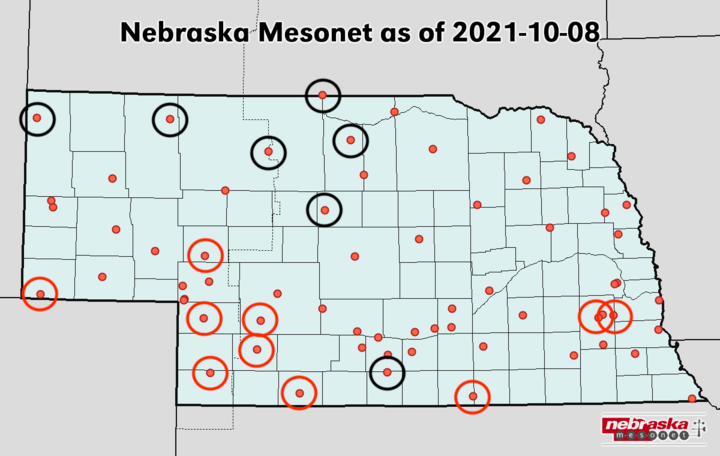

With money draining from their already-slender budget, Shulski and Cooper had little option but to plan and execute a strategic mass closure this year, beginning with stations unsponsored and/or located on private property. In the first round, they closed shop on mostly north-northwestern locations — Ainsworth, Gordon, Ragan, Dunning, Mullen, Sparks and Harrison (highlighted in black on Figure 2). The second round of closures will affect the entire span of southern Nebraska and the Panhandle (highlighted in red on Figure 2).

Additional closures around the state will depend solely on what kind of funding may be captured in the coming months. So far, new funding has been received via sponsors, who are coming forward to finance stations on the chopping block and stanch the funding gap. Mueller picked up the cost of the weather station in Wilbur when it was at risk of closure. His fellow educator, Laura Thompson, did the same — she’s currently keeping the lights on at the Rulo weather station.

While it’s urgently needed assistance, the sponsorship model just doesn’t generate enough money to overcome such substantial deficits, according to Cooper, who said a more stable source of funding is critical for the Mesonet’s viability.

Taking a page from a success story down south, Shulski said mesonet programs in states like Oklahoma are funded through state legislature. North Dakota’s mesonet is also thriving through state sponsorship, she noted.

“We have played all of our cards,” Cooper said. “At this stage, all we can do is collapse to a point of being able to pay bills and keep the paid-for stations viable and operating.

“The reality is, having it come directly from the unicameral or the UNL system would alleviate some of the funding pressures that are trickled down to individual departments. It’s burdensome for IANR to fund something of that scale, where everybody uses it.”

The proof is in the pudding — Shulski and Cooper shut off services as they watch sponsors fade and finances shrink, all the while knowing that if the Mesonet has a catastrophic failure, the domino effect will be felt far beyond the borders of Nebraska.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Shulski said. “If we’re not measuring weather variables, we can’t manage our extremes. We can’t be resilient. That is only going to get worse under climate change. It’s only going to become more important that we take these weather observations — not less.”