Late May and June 2020 have brought several days of excess heat and high winds with low humidity resulting in corn and soybeans using more water than normal. Combine that with the low rainfall levels and the crops on many afternoons are looking dry with that silvery look and some leaf rolling (keep in mind the water stress level when corn starts to roll it’s leaves is variety dependent). The result leaves every farmer wondering if they should have all the irrigation systems running or not.

Growers often start their center pivots early to incorporate fertilizer/herbicides or soften a soil crust to aid crop emergence and this year has not been an exception. Others, with furrow-irrigated fields, may make an early application, often before the crop actually needs much water, to consolidate the soil in the furrows so when the need for full irrigation comes the water will more easily run the full length of the furrows.

Aside from these non-irrigation applications, the question is, how much irrigation water will the corn need during the vegetative growth stage to produce optimal yields.

Growth Stage Irrigation Scheduling

Growth Stage Irrigation Scheduling for corn focuses on delaying irrigation and reducing nitrate leaching during the less sensitive vegetative growth period and fully watering during the critical reproductive growth stages. This strategy, called Water Miser, is based on research conducted by the University of Nebraska and elsewhere that shows corn is relatively drought tolerant during the vegetative period, but very sensitive to water stress during silking through early grain fill. Research conducted in the North Platte area has shown that irrigation could be reduced by 1 to 4 inches, compared to a fully irrigated crop, during the vegetative period without a significant yield reduction. Keep in mind that much of the water the corn is using during this growth stage is coming from the roots growing deeper each day into moist soil.

Reducing irrigation cost and lowering pumping are two important reasons to consider allowing moderate moisture stress on vegetative corn. Additional reasons include the possibility of lowering green snap potential and helping set the stage for easier irrigation scheduling. Reports have indicated that corn under moderate moisture stress has suffered less green snap compared to fully irrigated corn right next to it. Research studies have not been conducted to confirm this, but it does make some sense because the corn would be a little shorter and possibly less brittle.

Soil water monitoring data is easier to analyze if the crop has used some of the water in the 16 to 24 inch depth zone. The dryer zone can then be monitored with the sensors to see if the area gets wetter or dryer. If it keeps getting dryer, the irrigation system needs to keep running, however if it starts to get wetter, stop irrigating for a few days. Keep in mind that when irrigation is applied with a center pivot an inch at a time on the soil surface, the top foot will stay very wet all summer. Ideally the dryer zone should slowly expand deeper with the crop using most of the subsoil water by the time the crop matures. For more information on this scheduling strategy watch the Advanced Irrigation Scheduling Techniques video.

The Water Miser strategy focuses on delaying irrigation until approximately one or two weeks before tassel emergence for corn, unless the soil-water drops to 30% of plant-available water in the active root zone. Once the crop reaches the reproductive growth stage, the plant-available soil water (in the active root zone) should be maintained in a range between field capacity and 60% of plant-available water. Usually the soil is maintained one-half to one inch below field capacity to allow for rain storage. After the hard dough stage, the soil is allowed to dry to 40% of plant-available water to reduce pumping and provide drier fields for harvest.

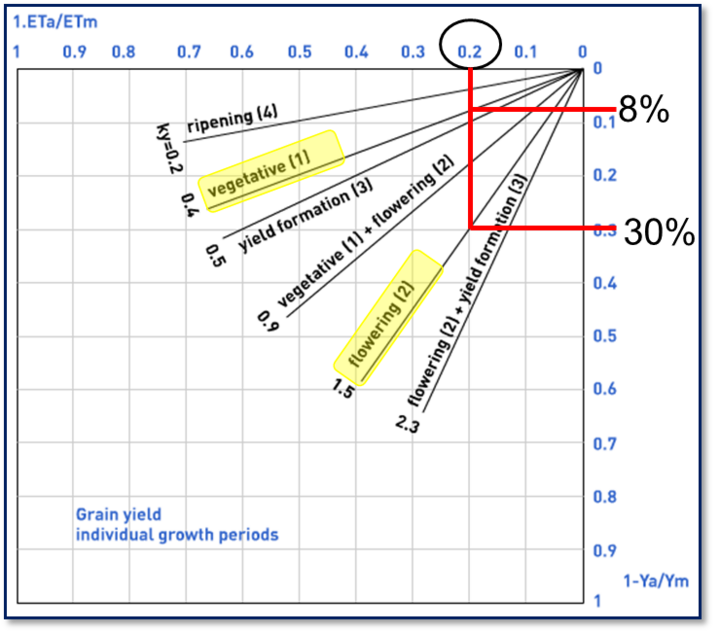

Figure 1, produced by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), shows the relative relationship between yield decreases and evapotranspiration (ET) deficits for individual growth stages of corn. The chart can be understood by knowing that the upper right hand corner represents a fully watered crop with full yield, thus no reduction of ET or yield; it is indicated by the zeros. The 0.5 on the top represents a 50% decrease in ET because of water stress and the 0.5 on the right represents a 50% reduction in yield. For example, a 20% ET deficit would result in an 8% yield decrease during the vegetative stage, whereas the same ET deficit would result in a 30% yield decrease during the flowering (silking) stage. The 8% yield decrease would be for a 20% reduction in ET from moisture stress for every day from the time the corn emerges up through tassel. This level of moisture stress is very unlikely to happen during the vegetative stage in a field in Nebraska that was irrigated the previous year, but could easily happen during the silking stage.

The past few weeks, leaf rolling during the heat of the afternoon has been common. Nebraska research suggests that some leaf rolling during the afternoons during the vegetative stage will not reduce yield significantly. Corn leaf rolling will often start in areas of soil compaction like field driveways or turn rows. These areas are usually small compared to the whole field, but are evident from the road. The bigger question is what is going on over the majority of the field. Soil water monitoring is an excellent way to know how much water is in the root zone and gives you, the producer, added confidence to delay irrigation.

In summary, research suggests that little irrigation is needed most years on corn during the vegetative stage to produce top yields in the eastern two-thirds of Nebraska on silt loam soils. Sandy soils or shallow alluvial soils with underlying sand, will need more irrigation of course, but keep in mind the research shows moderate moisture stress during the vegetative stage will not usually lower yields much if any. However, fields with lower capacity irrigation systems—especially in combination with sandy soils—will need to start prior to the reproductive stage to assure corn can be fully watered by tassel time. For more information about growth stage irrigation scheduling go to Irrigation Scheduling Strategies for Corn or Irrigation Scheduling Strategies When Using Soil Water Data video.