In Southwest and Western Nebraska, winter wheat was originally grown in a winter wheat-summer fallow rotation. Beginning in the 1970’s winter wheat was included in Ecofarming rotations with no-till corn or grain sorghum and summer fallow as a means to capture and maintain soil water through snow retention, increased infiltration, reduced evaporation, and weed control with herbicides instead of tillage. The 2 crops in 3 years instead of 1 crop in 2 years (the winter wheat summer fallow rotation) plus no-till resulted in being able to maintain or even increase soil organic matter levels. It requires approximately 2 ton of crop residue per year to maintain soil organic matter levels in this area of Nebraska.

Some are considering a spring wheat, corn, or grain sorghum rotation. Spring wheat may be seeded to replace the summer fallow period to produce extra income for these trying farm commodity prices. Crop producers have also used several spring seeded crops to replace the summer fallow in the 3 year system. Also, with increasing weed resistance to herbicides, the cost of summer fallow has become more expensive. The spring wheat will not have the yield potential that winter wheat has following a fallow period because of reduced soil water. Also, the spring wheat grain fill will be later than the winter wheat which can also reduce yield. Temperature during the filling period - over 85 degrees average – reduces yield in spring wheat.

Lower grain yields of spring wheat without a fallow period verses winter wheat after a fallow period has potential to reduce the following corn or grain sorghum yields due to lower spring wheat yields result in less crop residue than the more productive winter wheat, which could reduce the following corn or sorghum yield in the spring wheat stubble. One test, for example, where approximately over half of the straw was removed, the following corn yield was 20 bushel less.

How about following the spring wheat crop with winter wheat to increase the amount of crop residue for the following corn or grain sorghum crop? Volunteer spring wheat in the winter wheat crop next year may cause problems, but would not be expected. If any spring wheat volunteers produce grain, this may increase the possibility of downgrading of the winter wheat crop due to mixing of wheat classes. Results can be marketing problems and price discounts.

Hard red spring wheat (HRS) is grown mostly in the northern areas of the country where summers are generally mild and not too hot for young, tender plants. HRS is planted from March through late May and harvested in August or September.

The majority of the HRS – about 95 percent – is grown in the states of North Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, and South Dakota. Idaho and Washington also grow HRS. North Dakota accounts for slightly more than half of the annual United States HRS production.

The label "spring" or "winter" wheat refers to the time of year the seed is sown and sprouts. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) can be classified as winter or spring growth based on flowering responses to cold temperatures. Winter wheat is planted in the fall and harvested in the summer. This allows it to take advantage of fall rains and winter snow in areas that are very dry in the summer. This type of wheat has to be grown in places with more moderate winters and/or adequate snow cover for protection from extreme prolonged freezing temperatures. Most winter wheat require a period of cold dormancy before it will tiller and head - grow seeds or kernels. Hard winter wheat usually contains a lower protein content than spring wheat and is suitable for making bread. Farmers plant a wheat based on the optimal conditions for a region's climate and soil.

Wheat can survive relatively dry conditions but needs adequate moisture to germinate and for early growth. Spring wheat is generally grown where there are spring and early summer rains or in harsh winter regions where planting in autumn may be unfavorable. The wheat harvest is typically delayed in both crop types until the seed head grain's moisture content is at or below 13.5 percent.

How spring wheat develops

Spring wheat types do not require exposure to cold temperatures for normal development and can be planted in spring without concerns about vernalization. Winter wheat development is promoted by seedlings’ exposure for six weeks to temperatures in the 38 to 46 degrees Fahrenheit range. These types are usually planted in the fall, which exposes the seedlings to cold temperatures during late fall and winter.

Growing the Spring Wheat Crop

Seed selection, as with any crop, is an important first step. Getting the correct seed characteristics for your area and soil type is important. It is important to look at seed treatment for establishing germination that is disease free and protects against insects.

Prior to planting, any volunteer wheat, grass, or broadleaf weeds that are present need to be eliminated. This can be done through either tillage or herbicides. This will help both with competition for soil moisture and will reduce the effect of potential disease such as wheat streak mosaic or other wheat diseases that can transfer from weed species. Wheat streak mosaic virus requires a grass species host, such as established wheat plant. Timely herbicide treatment is essential to terminate weed growth ahead of seeding. Slower glyphosate action at low air temperatures makes it important to spray 3-4 weeks ahead of intended seeding for the best results. Unlike spring barley, you don’t need to wait for the ground to warm-up for wheat. Seed spring wheat as soon as you get decent seedbed conditions – the earlier the better. Seed into a seedbed that enables seed to soil contact to improve germination, while disturbing the least amount of soil possible when planting. University of Nebraska studies showed tillage can help speed up the process under dry conditions, and herbicides work better under wet conditions. Tillage causes soil water loss and destroys crop residues.

Soil fertility should be considered prior to seeding, taking into account the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium requirements for increased yield. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient for grain size, yield, and protein content. This is a controllable variable, unlike environmental conditions such as moisture and temperature. Nitrogen application timing is important to have plants that are well-established which supports faster plant canopy closure and weed control in the growing crop. Apply nitrogen to the seed bed, avoiding contact with the seed if applying greater than 30 pounds per acre with 7.5 inch drill spacing, with less amounts with wider drill spacing. It is advised to apply phosphate in-furrow at planting, preferably applied below the seed. Phosphorus deficiency in wheat is expressed as slow growing and late maturing plants. Potassium, sulfur, and other nutrients can be applied close to the seed at planting. Use soil tests results to determine fertilizer need and rates.

Spring wheat test weight, a measure of the quality of the wheat seed, is a minimum of 58 pounds per bushel, compared to the test weight of winter wheat of 60 pounds per bushel. Higher test weights have more extractable flour and less bran.

Through the years, winter wheat generally produces a third more grain than spring wheat when there is adequate moisture available. University of Nebraska variety trials from 1988 to 1992 for winter and spring wheat, winter wheat out yielded spring wheat by an average of 50% in the higher rainfall area in Eastern Nebraska, and a 25% increase in the drier Western Nebraska climate. As noted earlier, spring wheat heads fills later than winter wheat when the temperatures are higher. This results in lower yields. Residue production is similar in the two crop types, with the same “rule of thumb,” 100 pound of residue produced per bushel of grain produced. As spring wheat generally produces less yield, less residue will be produced in comparison to winter wheat. Commercial storage facilities will not blend winter and spring wheat. On-farm storage, direct marketing, and transportation costs are essential for spring wheat marketing. Based on futures spring wheat prices in Minnesota, spring wheat is generally $1.00 greater than winter wheat price, but we do not have a close proximity to those markets and transportation is costly. Nebraska’s spring wheat is usually going to have low quality as compared to spring wheat grown in Northern locations. Low test weight and poor protein quality are two of the major concerns. Check with your crop insurance agent to determine that amount of coverage that is possible for spring wheat.

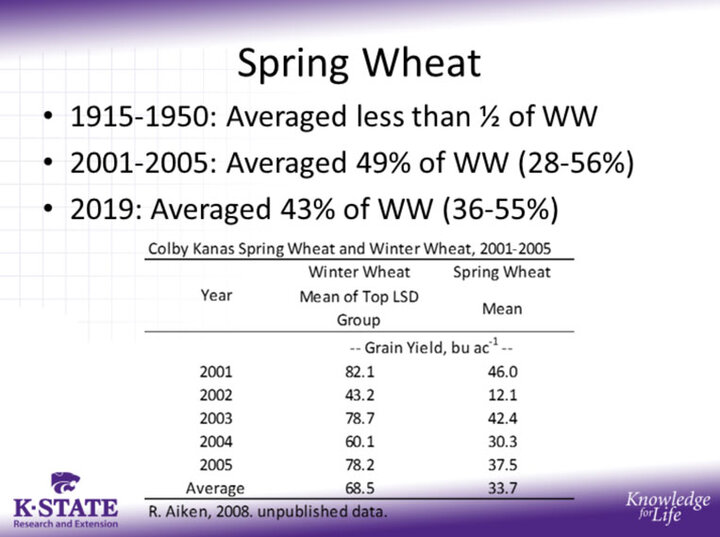

Following are results comparing spring and winter wheat yields in Kansas and Nebraska.

Both spring and winter were summer fallow wheat.

Following are University of Nebraska data comparing winter wheat yields with spring wheat yields. The University discontinued Spring Wheat trials in the 1990’s.

| Bushel | |

|---|---|

| Winter Wheat – Saunders County | 60 |

| Spring Wheat – Saunders County | 26.9 |

| Winter Wheat – Cheyenne County | 25.0 |

| Spring Wheat – Cheyenne County | 38 |

| Bushel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Year | 3 Year | 4 Year | 5 Year | Average | |

| Winter Wheat – Saline and Saunders County | 41 | 43 | 70 | 47 | 50 |

| Spring Wheat – Saunders County | 18.5 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 16.9 | 17 |

| Winter Wheat – Cheyenne, Deuel, Scottsbluff, Box Butte County | 39 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 39 |

| Spring Wheat – Cheyenne County | 39.8 | 28.9 | 25.9 | 21.9 | 29 |

A partial budget comparing Spring Wheat and Corn, Corn rotation with summer fallow, Winter Wheat and Corn.

Spring Wheat – Corn Rotation

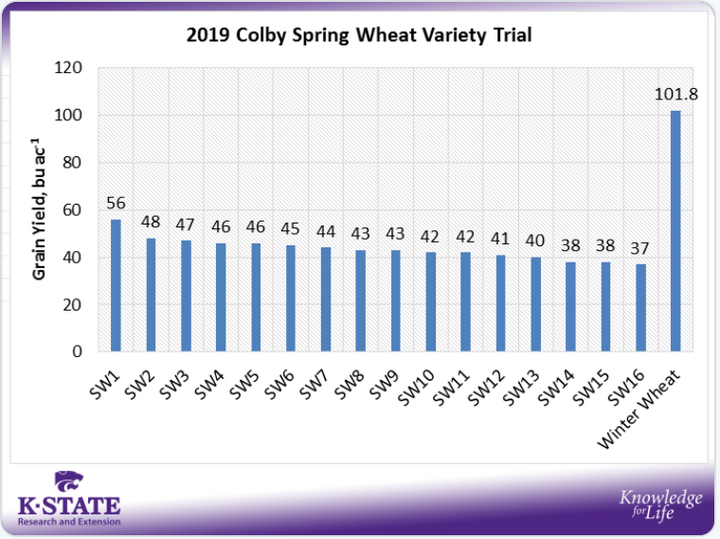

For spring wheat yields we are using the average of the 16 varieties in the 2019 Colby, Kansas Spring Wheat Variety Trial. As noted in the chart, these yields were with summer fallow. The productions costs are based on the 2020 Nebraska Crop Budgets.

| Loss / Acre | Profit / Acre | |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 Spring Wheat Production Cost $220/acre @43.5 bushel/acre = $5.06/bushel Estimated Value $3.50/bu because of access to markets |

$68.00 | |

| 2021 Corn Production Cost $320/acre @100 bushel/acre = $3.20/bushel |

$30.00 | |

| 2-year loss $38.00/acre | ||

Fallow – Winter Wheat – Corn Rotation

| Loss / Acre | Profit / Acre | |

| 2020 Fallow - Cost | $60.00 | |

| 2020 Fallow - Land and Real Estate tax | $70.00 | |

| 2021 Winter Wheat Production Cost - $280/acre @80 Bushel yield |

$40.00 | |

| 2022 Corn Production Cost - $350/acre @130 bu/acre = $2.70/bushel |

$104.00 | |

| $130.00 | $144.00 | |

| 3-year profit $14.00/acre | ||

Note: Production costs include a return to land, real estate tax, overhead and labor cost.

The above is an example. One should put in their estimated costs, estimated costs, and estimated yield and crop values.

For comparison, see the Article following on “How Late Can You Seed Winter Wheat and Still Produce Grain?”