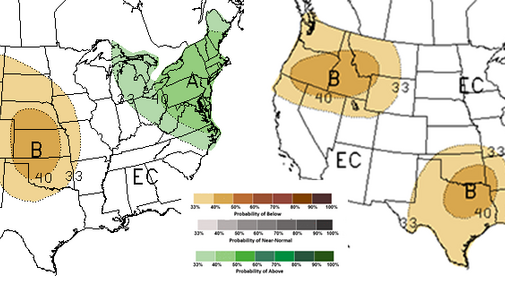

The Climate Prediction Center’s March 15 outlook continues to favor dry conditions for the Southern Plains. Its summer precipitation outlook, however, has changed and is shifting the highest probabilities for below normal moisture south (Figures 1 and 2).

Although significant dryness has been taken out of the summer forecast across Nebraska for now, the extreme dryness in the Southern Plains and poor snowpack across the southern Rockies are still concerning for our neighbors heading into spring planting season. Even with the storm activity this past week, significant moisture stayed north of the Kansas-Oklahoma border.

In a normal atmosphere devoid of dry surface conditions, moisture pivoting around upper air lows moving toward the central U.S. from the southern Rockies will usually produce significant moisture on the north and east side of these systems. We saw this with the past two upper air lows crossing the region.

The big difference between these systems and those working on normal atmospheric moisture is the amount of dry air from the Southern Plains that was pulled into the low-pressure circulation. As the dry air wrapped around the low, precipitation fell in two distinct bands north of both low-pressure systems.

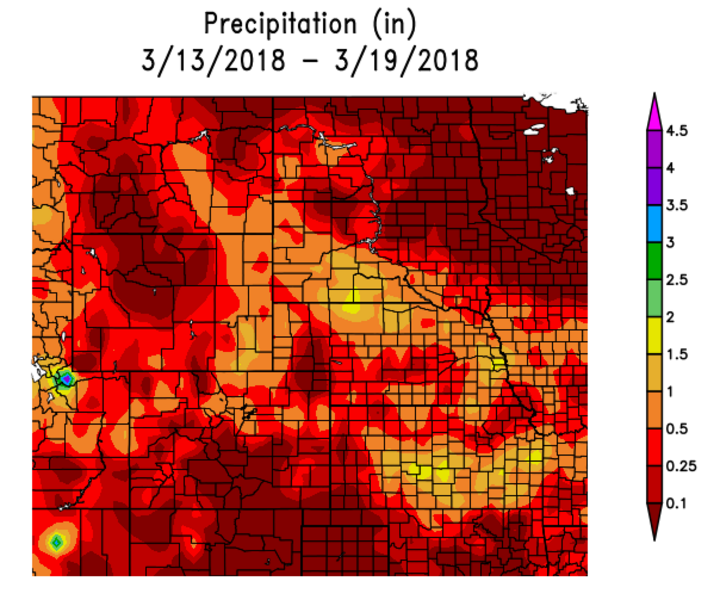

The first systems dropped heavy rainfall across northern and parts of southern Nebraska, with light totals across central Nebraska. The second system ejected on a more southerly track, but a similar precipitation shield was noted. Precipitation was heavy across north central and south central Kansas, with a distinct dry slot visible in total storm output (Figure 4).

Southern Drought and Impacts on Wheat

It has been over six months since these areas of Kansas have received more than an inch of moisture in a 24-hour period. The rainfall should replenish top soil moisture (top foot), but more will be needed on a regular basis. Although some of the most southern Kansas locations are approaching or have reached jointing, the crop is probably 14 days away from widespread jointing. Oklahoma reached 21% and is about a week away from more than half the crop reaching jointing.

If we look at the area impacted in Kansas from the second upper air low, the core areas of one inch plus values fell across the northern half of the South Central Agricultural district, southern half of the Central Agricultural district, and the northern half of the North Central Agricultural district. These three districts accounted for 55% of the five-year wheat production average, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Only about half of the area in these three districts received more than an inch of moisture, or in simpler terms, 25% of the winter wheat production area of Kansas received rainfall that has the potential to give them another 7-10 days of moisture before topsoil moisture is depleted. A week of above normal temperatures will shorten this period, while cooler than normal temperatures will extend it.

Once jointing is reached, the crop will be at close to evaporative demand (i.e., Potential ET and Crop ET will be equal if water is not limiting). Therefore, an active pattern can still save the crop acres that have not been abandoned, but the western third of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas are rapidly approaching the point where fields may be abandoned.

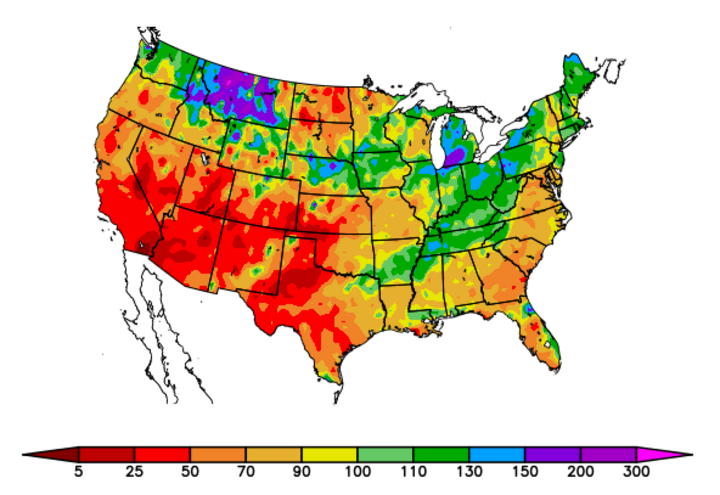

While we have been documenting the ongoing drought across the Southern Plains for almost five months, the hope was that snowpack levels would begin to show improvement and help contribute to a more aggressive precipitation pattern across southern High Plains region. Unfortunately, snowpack levels continue to disappoint and remain well below normal (Figure 3 and Figure 5)

With the statistical peak of the southern Rockies occurring between mid-March (central New Mexico) and mid-April (southern Colorado), there is no more time left in the snow season for significant recovery. Temperatures at lower elevations are beginning to increase dramatically, with 70s and 80s forecasted to return to the region as early as this weekend.

It is this heat that will need to be watched closely for northward expansion into the central Rockies as we proceed through April. Although the central Rockies (including the Platte headwaters region) is below normal, it is not as dramatic as southern Colorado. However, most of the below normal snowpack readings are low elevations, while normal to above normal snowpack values are located at the higher elevation monitoring sites.

It is entirely possible that additional snowpack gains could still bring the central Rockies snowpack back to a normal range (80%-120% of normal). The lack of low elevation snowpack, however, indicates an inherent risk of earlier than normal loss due to melting if above normal temperatures spread north out of the southern Rockies.

Potential for a Stormy Spring

It is also important to note that La Nina spring conditions usually entail an active severe weather season for the southern and central High Plains. At present in the central US there is very cold air in the upper half of the atmosphere. We are just lacking the surface heating necessary to create unstable atmospheric conditions.

If southwest storms continue to move in our direction as they have the past three to four weeks, we will likely experience widespread severe weather outbreaks, including tornadoes and hail. This scenario would likely lead to some planting delay issues, particularly during the first half of spring. The question that can’t be answered with confidence is whether recent precipitation is just a temporary blip in an overall dry pattern.

If we return to the large eastern U.S. trough pattern experienced during the first two months of winter, cold fronts pushing southward out of Canada on the backside of the upper air trough would be more likely to produce severe hail events with minor tornado development. Tornadic development would occur along the cold front during peak heating hours, but typically these are short lived once the entire line merges into a single thunderstorm front.