Dean Stevens well knows the value of getting a bird’s-eye view of his corn and soybean fields to assess plant health, wind damage, and pest threats – problems that, in their initial stages, may be difficult to assess on a field scale from conventional scouting.

Grant Application Tips from the Stevens

“We really enjoyed the online application process,” said Deb of applying for their NCR SARE producer grant, noting however that it represented the culmination of a good deal of research and planning. In addition to helping facilitate the application process, Deb will help plan and coordinate an annual field day, administer the grant funds, and work with media to provide education about the research project. That role is a natural fit for Deb, who was an Extension educator in southeast Nebraska before turning her attention full time to family and farm.

The Stevens offered several tips to growers interested in applying for the NCR SARE Producer Grant Program.

- Plan plenty of time to work on the application. Dig deep into the details to get your ducks in a row and ensure your budget covers all your costs.

- Enlist the help of professionals to help plan the research protocol so it will provide reliable, quality results. The Stevens are using a scientific randomized and replicated research design to compare the traditional N application with a sensor-based approach. (The Nebraska On-Farm Research Network offers advisors and resources for growers interested in conducting on-farm research.)

- Determine the standards you’ll follow and how you’ll integrate them into your field and research operations.

- Be realistic in your plans, how you will approach the field operations, and what you can get accomplished. For example, with the Stevens project some days it was too windy or too cloudy to get reliable imagery and they needed to rely on their back-up plan. You have to take all these things into account to know what’s feasible and how you can still accomplish the research, Stevens said.

Grant Webinar with Live Q&A October 17

If you’re interested in applying for a Farmer Rancher Grant, learn more during the October 17 SARE Farmer Rancher Grant Webinar with live Q&A.

NRC SARE Coordinator Joan Benjamin (573-681-5545) and Miranda Duschack, small farm specialist, Lincoln University Cooperative Extension, (314-604-3403) will present on how to write a strong proposal and project budget and where to get help. The online session will be from 7 to 8:30 p.m. CDT.

Additional details on applying for an NCR SARE Farmer Rancher Grant are available on the NCR-SARE website, including tips for writing a grant proposal and a database with information on previous farmer rancher grants in the 12-state North Central Region.

The application deadline for the Farmer Rancher Grant program is 4 p.m. Dec. 7.

For more informaton about SARE in Nebraska visit the program website or contact Nebraska State Coordinator Gary Lesoing (402-274-4755). Lesoing, who has been involved in research and education in sustainable agriculture since 1980, is also a Nebraska Extension educator in southeast Nebraska.

Stevens, who farms near Falls City in southeast Nebraska, started aerial scouting his fields from small planes in the 1990s, taking photos to document plant health and wind damage. In the early 2000s he got his sport pilot license and moved to a two-seater powered parachute to do aerial scouting (Figure 2). (View a 2016 flight online.) Flying just 30 to 100 feet above the crop allowed him to view fields more personally and evaluate stands, water needs, soil nutrition, and pest pressures, taking photos that he shared with his crop consultant. Together they used the data he gathered to address problems in the field.

Now, with the support of a Farmer Rancher Grant from the North Central Region Sustainable Ag Research and Education Program (NCR-SARE), Stevens is keeping his feet planted on the ground while a drone outfitted with infrared sensors (Figure 3) scouts his fields each week, providing key data that can be used to develop prescriptions for targeted, precise in-season nitrogen applications.

The NCR-SARE On-Farm Research

A longtime advocate of on-farm research, Stevens has been conducting field trials on his farm since 1974 when he graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln with a major in soil science. He has evaluated crop hybrids, fertility, population, seed treatments, fungicides, and nitrogen applications. In 2016 Dean and his wife and farming partner Debra applied for and received a $15,000, two-year NCR-SARE farmer/rancher producer grant to study how to conserve nitrogen use in corn production by applying more N in-season, based on crop need. The project is:

- assessing cutting-edge technologies for determining optimum nitrogen rates;

- demonstrating the efficiency of applying a higher percentage of nitrogen in-season; and

- using variable rate technology to apply precise nitrogen rates, based on data gathered from drone mounted sensors.

This year, in the first year of the grant, the Stevens established their research study in a bottomland rainfed field of silty clay loam with some silt loam soils. They’re testing their current preplant nitrogen rate (160 lb/ac N) and two lower rates (100 and 75 lb/ac N), replicating each rate four times. By applying more nitrogen in-season, they can respond to each season's specific conditions. For example if early mineralization is higher than normal, the in-season N application rate can be decreased or if early season rains may have leached some nitrogen, rates can be increased.

Good stewardship is also an important aspect of moving more of the nitrogen application to in-season based on plant need, Deb said, noting the practice could provide both environmental and economic benefit.

Gathering Plant Data via the Drone

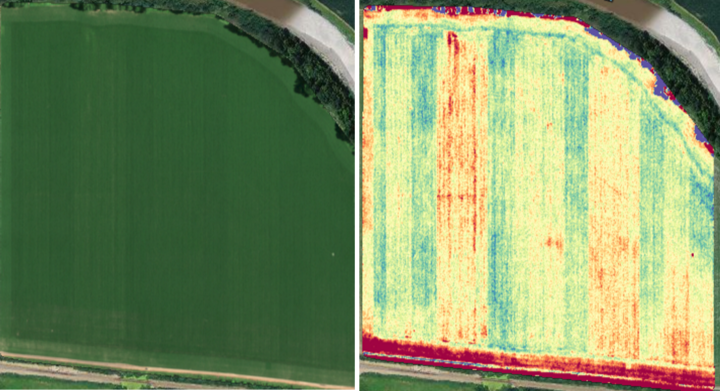

To assess the effect of the different rates on plant nitrogen, a drone outfitted with infrared sensors was flown weekly over the field trials by daughter and son-in-law Laura and Nathan Thompson, both of whom have FAA remote pilot certificates. The sensor data was then coupled with two algorithms and the Hybrid-Maize models to calculate the optimal in-season nitrogen rate for each strip.

“The imagery indicated deficiencies before my eyes could detect it,” Stevens said. “We monitored the fields closely and planned the in-season nitrogen we would need to reach our full yield potential.”

“As we suspected, there was a lot of variability across the field in nitrogen need,” Stevens said. Applying fertilizer based on the infrared imagery (Figure 4) may not necessarily mean less nitrogen is applied, but rather that what is applied is targeted to exactly how much is needed, where it’s needed, and when it’s needed, increasing nitrogen use efficiency and reducing the potential for nitrogen loss.

The corn was too high for a sidedress application and Stevens worked with an aerial applicator who could make precision applications of dry urea to individual test strips.

Traditionally growers might use a predetermined rate and time of application or wait until the plant’s need for nitrogen was visible, which might cost the grower potential yield, Stevens said. Using the infrared imagery provided by the drone flights allowed earlier detection of plant nitrogen needs so they could be addressed before yield was affected.

“We provided the aerial applicator a variable rate prescription and within each pass they changed the rate according to the plan.”

Adopting the drone technology had its challenges, but was made easier with some “high tech children,” Stevens said. Daughter Laura, a Nebraska Extension educator for agricultural technologies, is also a coordinator for the Nebraska On-Farm Research Network, and Nathan works in agriculture. Also contributing to the project through development of educational events is Gary Lesoing, Nebraska Extension crops educator with responsibilities for Nemaha and Richardson counties.

“This technology is still in its infancy with multiple firmware and software updates required for almost every flight,” Stevens said. “It’s not just plug and play. To record the imagery correctly, it’s a little more difficult.”

Each flight may have as many as 4,000 single photos that need to be stitched together to create a single, high-resolution image of the field, Stevens said. This compilation is done in the digital cloud by a commercial firm specializing in agricultural uses of drone imagery.

Flights also aren’t necessarily a one-person job. Drone pilots are required by the FAA to keep their eye on the drone at all times, while also piloting the drone from a screen, Deb said. While the drone flies a pre-set pattern to criss-cross the field, it can still be helpful to have a two-person crew.

“When you’re flying a drone at 300 feet in the summertime, you have to keep an eye and an ear toward sprayer planes,” Dean said. There were several flights where they maneuvred their drone to the ground as a sprayer plane moved from one neighbor’s field to another, crossing their flight path.

Next summer, during the second year of the grant, the research will continue on the Stevens farm and be initiated on Dale and Ronda Yoesel’s neighboring crop and dairy farm, allowing the on-farm researchers to collect data from two different fields with similar research protocols and management.

Follow Their Research

Results from the first year of the project will be shared this winter when the Nebraska On-Farm Research Network hosts meetings to report data gathered and lessons learned by participants in 2017. In summer 2018 the Stevens will share further information about this project at a field day. The Stevens have two Twitter accounts where you can follow information on this project, as well as other aspects of their family farm, at @GoodLifeAgDeb and @thegoodlifeag.

To learn more about on-farm crop research projects in Nebraska visit the Nebraska On-Farm Research Network page in CropWatch or follow @OnFarmResearch on Twitter.