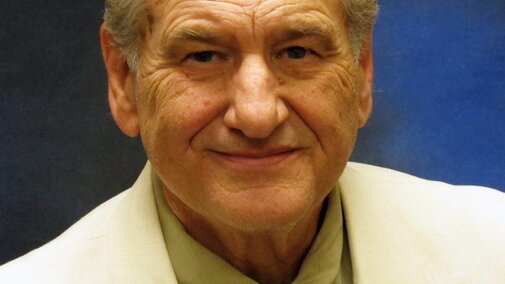

Alexander Pavlista’s retirement at the end of March marks the end of 50 years of research, 29 of them at the University of Nebraska Panhandle Research and Extension Center at Scottsbluff. A Nebraska Extension specialist and professor in the Department of Agronomy and Horticulture, Pavlista was the university's lead potato expert.

Pavlista knew he wanted to be a scientist at an early age. He was 13 when he knew he wanted to do scientific research, 15 when he picked biology, 21 when he chose biomedical research over oceanography. He chose plant physiology, and by age 30 knew he wanted to use science in the service of agriculture.

Born in Praha, Czechoslovakia, he left the country in 1948 when his parents escaped the Communist regime there and migrated to the United States. Growing up in New York City, he attended Manhattan College, where he received a bachelor’s degree in biology with minors in chemistry and theology.

He received a Ph.D. in plant physiology at City University of New York after two years at Oak Ridge National Laboratory as a National Institute of Health research trainee.

In 1988 Pavlista was hired as the potato specialist and crop physiologist at the UNL PREC at Scottsbluff. Prior to that he spent two years as a USDA research associate at North Carolina State University and nine years as a research biologist at American Cyanamid.

Nebraska Extension potato specialist

At the Panhandle Center, Pavlista developed connections to the potato industry on the local, state, and national levels. In 2004 Pavlista and his wife, Victoria, hosted the Potato Association of America (PAA) meeting in Scottsbluff and in 2008 he served as PAA president. In 2015 he was awarded an Honorary Life Membership in PAA.

A collection of his research has been published online as the Potato Education Guide, a comprehensive, practical guide on potato varieties; soil management; insect, disease, and weed management; irrigation; physiological disorders; and production practices.

The guide was one of the earliest and most extensive collections of research-based information for farmers offered by Nebraska Extension. Originally housed at the Panhandle Center’s website, it since has been migrated to Nebraska Extension’s CropWatch.unl.edu, a central information resource for Nebraska agricultural crops.

For many years Pavlista also published a newsletter, Potato Eyes, which is archived on the website.

During his career Pavlista has seen a number of changes in Nebraska’s potato industry (see box). Yields have increased, thanks to research on production practices such as improved pest control, irrigation scheduling, and sulfur fertilization, as well as development of new varieties.

As part of a team of research and extension specialists at the Panhandle Center, Pavlista has also studied other crops, such as wheat, canola, fenugreek and corn, and has explored new markets and new crops.

Reflecting on his career, Pavlista is reluctant to dwell on his accomplishments. From the farmers’ perspective, Pavlista said, an important area has been chemical management of crops. He has conducted research into areas such as sulfur fertilization for disease control, pesticide use, and limited irrigation.

Scientific inquiry, which captured his imagination at age 13 and drew him to agriculture, has led to some career highlights. One of these is research into plant growth regulators. Pavlista has studied the effects of gibberellic acid (GA), a plant hormone that regulates growth and development.

Pavlista has studied GAs effects in several crops for several purposes. One of these is changing plant architecture, for example by providing more upright dry edible bean plants that facilitate direct harvest.

Another is speeding early development of winter wheat, thus allowing later planting dates to accommodate rotations with summer row crops.

In retirement, Alex and Victoria will be living in Denver, relaxing with puzzles, games, and reading; staying active by skiing, swimming and walking; and writing. He also has been granted emeritus status by the promotion and tenure committee in the UNL Department of Agronomy and Horticulture.

Changes in Nebraska's Potato Industry

Growth of the Nebraska Potato Industry, written by Pavlista and published in 2016 as a Nebraska Extension NebGuide (G2272), traces industry fluctuations over 149 years in the areas of acreage, yields, production, value, and markets.

Potato production was first tracked in 1866, the year before Nebraska became a state, by the Nebraska Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). That year, potatoes were grown on 5,000 acres, yielding 36 hundredweight per acre. The total crop value was $500,000.

Between 1866 and today, there have been a number of ups and downs. From 1907 until the 1930s, acreage plateaued at around 100,000 acres. The Dust Bowl and Great Depression caused the number of acres to decline by more than one-third, leveling off at about 70,000 acres through World War II. After the war, acreage declined for decades, hitting a low point of less than 7,000 acres in the 1970s, before recovering modestly to its present level of 13,000 to 14,000 acres.

As acreage has declined, however, the state’s total production has mostly grown. In the early 1920s, with 140,000 acres, production was 7.0 million hundredweight. During World War II, acreage was down to 70,000, but growers produced as much as 7.5 million hundredweight. Since 2000, production has hovered between 8 million and 10.5 million hundredweight, from less than 20,000 harvested acres.