Horseweed (marestail, Conyza canadensis L.) is a unique weed species that can emerge in both fall and spring. In Nebraska, unlike the eastern Corn Belt, horseweed populations predominantly emerge in fall as a winter annual.

Horseweed is native to North America; however, until the broad-scale adoption of no-till it was generally not considered a significant agronomic weed. Since horseweed is a surface-germinating weed species, tillage is an effective control mechanism. However, in the 1990s the widespread adoption of glyphosate-resistant crops and no-till gave this weed opportunity to invade. In less than four years after the introduction of glyphosate-resistant crops, horseweed evolved resistance to glyphosate in Delaware. Since then, glyphosate-resistant horseweed populations have been reported in over 18 states including Nebraska, where it was first confirmed resistant to glyphosate in 2006.

Figure 3. Horseweed regrowth following burndown herbicide application.

Why is horseweed a problem?

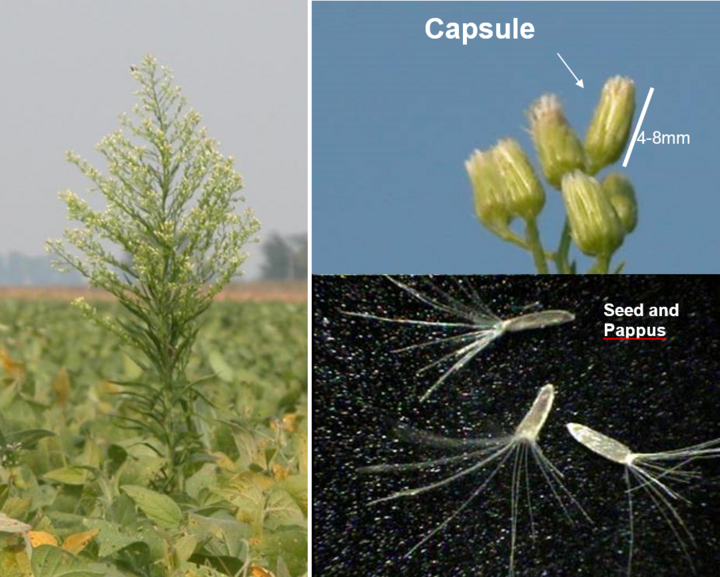

Horseweed’s long emergence window makes it unique from most other annual weeds. It can emerge for up to nine months of the year in Nebraska. Horseweed is small seeded with a dispersal mechanism called a pappus (Figure 2), allowing the seed to disperse in the wind over long distances. Horseweed is predominantly self-pollinated, allowing it to easily spread into new areas where it can produce lots of seed and rapidly establish in new fields. Lastly, horseweed has been known to quickly evolve resistance to many herbicide modes of action, including glyphosate, atrazine, paraquat, and ALS inhibitors.

Identification

Horseweed seedlings have oval shaped cotyledons and the first true leaves form a rosette (Figure 1). Horseweed leaves range from hairless to densely covered with short hairs. In the bolting phase, horseweed is an erect plant and can have one or more stems forming seed heads. Often, unsuccessful burndown herbicide applications will result in horseweed re-growing from multiple stems (Figure 3). Mature plants can range in height from 2 to 10 feet and can produce more than 1,000,000 seeds, although when growing in competition with soybean, seed production generally does not exceed about 60,000 seeds.

What can we do about it?

To manage horseweed, growers should incorporate crop rotation (as horseweed is predominantly a problem in soybean) and/or use tillage where appropriate. Burial of the seed can lead to significant reduction in germination. The best time to manage horseweed populations is prior to or just following germination. In soybean and corn production fields in Nebraska, this means using fall-applied herbicides. In situations where horseweed has germinated, growers should utilize multiple effective herbicides in tank-mixtures.

Since most of the troublesome horseweed populations are in glyphosate-tolerant crop production fields, it is best to assume some level of glyphosate resistance is present. This means that two herbicides in addition to glyphosate should be used whenever possible. For burndown applications, growth regulators, paraquat, ALS-inhibitors or a triazine herbicide can be used. For greatest efficacy, burndown herbicides should be applied under favorable weather conditions (above 50°F and low winds). Residual herbicides also can be an effective tool for managing horseweed, particularly at planting of corn and soybean. Postemergence in-season herbicide applications are difficult, especially in soybean, as herbicide options are limited and horseweed plants are typically larger.

Herbicide Options

For specific herbicide options to manage horseweed in corn, soybean and fallow fields, consult the 2017 Guide for Weed, Disease, and Insect Management in Nebraska, available in print and digital versions from the Nebraska Extension Marketplace. (The print version is expected to be available in early to mid January.)