After more than 10 years of research and development, University of Nebraska researchers have registered a new chickpea cultivar that offers enhanced disease resistance and production potential. The chickpea’s name — New Hope — well reflects their optimism for its value to producers, particularly in western Nebraska where disease has reduced production.

“This chickpea represents a new option for growers in the Panhandle. Its disease resistance means they could grow chickpeas without having to make three to four fungicide treatments a season,” said Carlos Urrea, dry bean breeder in the University of Nebraska Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

In the early 2000s there were 10,000 acres of chickpeas in the Panhandle, Urrea said, but that number dropped precipitously as growers faced significant losses to blight. In recent years the number of acres has been increasing and was close to 1,000 acres in 2016, Urrea said.

New Hope, a large cream-colored kabuli chickpea, was selected specifically for adaptation to Nebraska growing conditions and for enhanced resistance to Ascochyta blight, caused by Ascochyta rabiei (Pass.) Labr. The new cultivar was announced in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Plant Registrations in an article by Urrea, University of Nebraska-Lincoln associate professor of agronomy and horticulture, Fred Muehlbauer, research geneticist and plant breeder at Washington State University, and Robert Harveson, UNL professor of plant pathology. Both Urrea and Harveson are at the NU Panhandle Research and Extension Center at Scottsbluff.

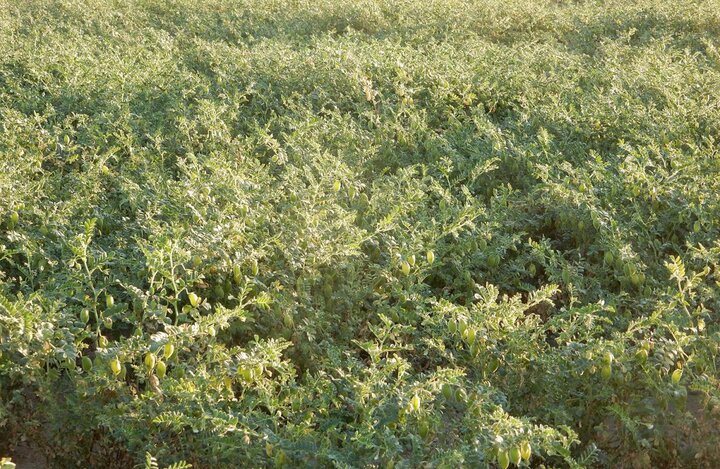

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), known in the US as the Garbanzo bean, is grown in 57 countries and is the third most important food legume in the world. New Hope is a mid-season chickpea that matures 105 days after planting. It has an upright indeterminate growth habit, averages 43 cm in height, and has excellent lodging resistance. It has a compound leaf structure and white blossoms.

Ascochyta blight can limit chickpea’s yield and quality, the latter affecting its marketability. The authors write that “Growers can minimize the disease’s impact by using moderately resistant cultivars integrated with strategic agronomic management practices such as disease-free seed, seed treatment, crop rotation, tillage, and foliar applications of fungicides….”

Of these options, planting resistant cultivars is the most cost-effective means for managing the disease within an integrated pest management system, the authors wrote.

Chickpea has potential as an alternative crop in western Nebraska because it fits well with growers’ existing equipment, capabilities of dry bean processors, and regional infrastructure, Urrea said. It is assumed to be adaptable for other areas of the chickpea production area in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana.

Urrea said they are in the process of applying for cultivar protection under the US Plant Variety Protection Act through the Husker Genetics Foundation Seed Program at the University of Nebraska. After that its expected that the variety will be licensed to a commercial company to grow the stock and start increasing the seed. It should be available to growers for the 2019 season.

This research was conducted with financial support from the Nebraska Dry Bean Commission, the Nebraska Department of Agriculture through the Specialty Crop Block Grant Initiative, and the national Hatch Project.

For more information about the authors’ research and New Hope’s level of disease resistance, download the full article, Registration of 'New Hope' Chickpea Cultivar with Enhanced Resistance to Ascochyta Blight, in the Journal of Plant Registrations.