This is one of several briefs on NU cover crop research featured in this week's CropWatch.

Background

Cover crops in corn and soybean systems can reduce soil erosion, mitigate nutrient loss, improve soil physical soil properties, and increase yields. High biomass production is key for cover crops to fulfill these functions, but may not be attainable due to the short window of opportunity for winter cover crops in Nebraska corn and soybean systems. Cover crops may negatively impact subsequent crop yields if they leave soil water deficits or immobilize nitrogen upon their decomposition.

With this study we wanted to determine the feasibility and impact of winter cover cropping on soil quality, soil water, and crop yields in corn-soybean systems across Nebraska. Our objectives were to quantify cover crop emergence, fall and spring biomass production, soil water changes, soil chemical and physical property changes, and crop yields.

Study Description

Experiments were carried out at four University of Nebraska research sites. The two irrigated studies were at the South Central Agricultural Laboratory (SCAL) near Clay Center and the West Central Research and Extension Center at North Platte. The two rainfed studies were at the Agricultural Research and Development Center near Mead and the Haskell Agricultural Lab (HAL) near Concord. Five types of cover crops were grown:

- cereal rye (alone, at 60 lb/ac),

- forage radish (alone, 7 lb/ac),

- a mix of hairy vetch and winter pea (25:10 lb/ac, respectively), and

- a mix of cereal rye, forage radish, hairy vetch and winter pea (30:10:4:3 lb/a).

Cover crops were planted either early (broadcast into corn or soybeans when corn was at the half-milk stage) or late (drilled after corn or soybean harvest) in each of the following rotational sequences:

- continuous corn (CCC),

- soybeans followed by corn (CSC), and

- corn followed by soybeans (SCS).

All cover crops were terminated with glyphosate two weeks before planting of corn or soybeans. Variables measured included cover crop emergence, fall and spring biomass production, soil nutrients (N, P, K and organic C), bulk density, aggregation, water infiltration, soil water, and crop yields. Only data from SCAL and HAL is shown, for 2015/2016.

Applied Questions

Which cover crops produce the most spring biomass?

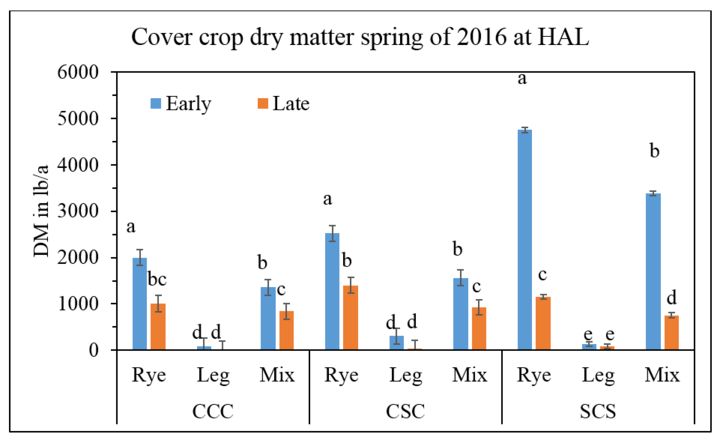

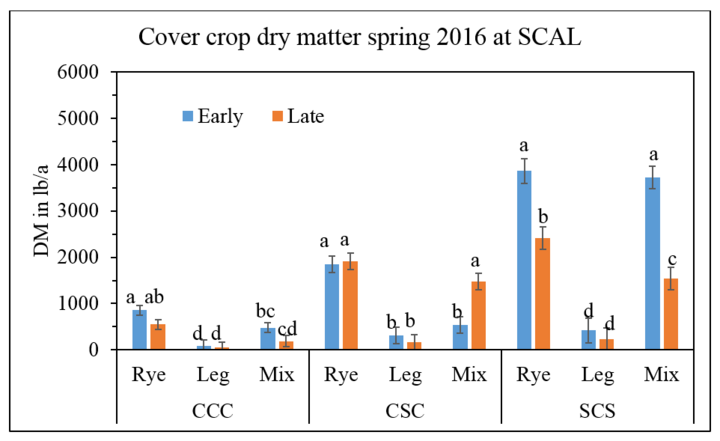

Cover crop biomass production for each species varied with planting date and rotational sequence. Cover crops grown after corn and before soybean (SCS) had the highest overall biomass production at each location, as cover crops were terminated two to three weeks later.

At HAL in northeast Nebraska cereal rye produced the most biomass (up to 4,800 lb/ac in SCS) and legumes always produced the least (up to 300 lb/ac) (Figure 1). Forage radishes winterkilled. Thus, the mix biomass was mostly rye and can be thought of as rye planted at 30 lb/ac instead of 60 lb/ac. The mix had less biomass than rye.

At SCAL in south-central Nebaska biomass of the rye was similar to that in the mixture. Legume biomass was low (Figure 2).

Which planting date resulted in the most spring biomass?

At HAL, in each rotational sequence, early planting resulted in higher spring biomass for rye and for the mixture, but not for the legumes (Figure 3).

At SCAL, early planting was only beneficial in cover crops before soybean (SCS). For cover crops growing in continuous corn or corn-soybean-corn (CSC) biomass production was the same, whether planted early or late. The late planting was drilled, and improved seed-soil contact might be beneficial in this drier environment.

What were the impacts on crop yields?

The largest impact on corn yields was whether the corn was grown in rotation.